Den fördolda historien

Sofi Okanens tal Stavanger 23/8-2016

Is This How We Will Be Remembered?

By Sofi Oksanen Analysis, Culture, Estonia, Finland, Literary September 23, 2016

Is This How We Will Be Remembered?

The small boat Triina left Tallinn on 19 September, with about 450 Estonians and 80 coastal Swedes on board. Photo: Estonica.org

The only person from my Estonian family who fled to the West during World War II, was a young man who had just turned 18. You may wonder why he was the only one. Since the refugee crisis started, the same question has been popping up in Finland over and over again: why there are so many young men coming, and so few women and children?

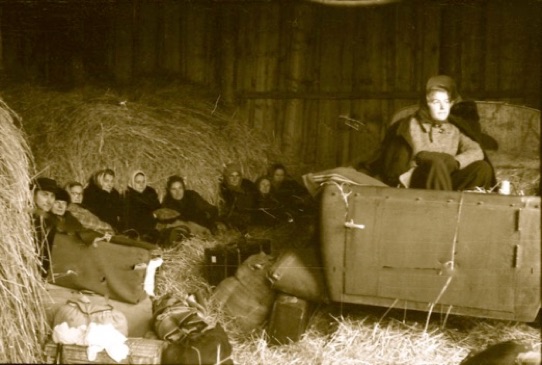

Because our family didn’t have enough money, that young boy was the only one who they could afford to help. Fleeing was very expensive back then – just as it is today. And if you have little money, it’s obvious who will be chosen to escape. It’s always the young boys and men – those who would be forced to join the army, the army of the enemy. According to international law, it is illegal for occupying forces to recruit locals, but nobody cares about those rules during war. During World War II, Estonia was occupied twice by the Soviets, once by the Germans, and they all wanted Estonians to join their ranks. The young man’s mother collected everything she could to get her son away, this time, to escape the German army.

My grandmother would’ve wanted to flee as well. But there were multiple reasons for why she didn’t. My grandfather was hiding in the forest – he was a Forest Brother who wouldn’t leave his country, let alone join the enemy ranks, and was ready to resist. She had small children, little money, and was horrified by the idea of crossing the sea in a small boat.

But this particular young man managed to flee, and he first went to Finland, where he saw his name on a poster at the railway station. The poster listed the names of wanted Estonians who were considered criminals for avoiding conscription, so he decided to find a ship to take him to Sweden. The ship sank, yet he was a young man with a young man’s strength, and managed to reach the shore by hanging onto a piece of timber. He didn’t know if anyone else had been able to save themselves, but he had. Young men tend to survive shipwrecks better than women, children and the elderly.

However, he didn’t stay in Sweden – it was too close to the Soviet Union. At the time no one knew how far the warring enemies would go or if they would cross Swedish borders as well. He kept moving and ended up living in the United States. He didn’t dare tell anyone in Estonia that he was alive until the 1960s, when he sent a letter to his mother who was overcome with joy. He started to regularly send chiffon scarves to her which were just thin enough to fit into an envelope. In the Soviet Union these fashionable scarves were hard to get, so she could sell them for a good price. The scarves really helped her – she couldn’t get a good job in the Soviet Union because she was from the wrong family, and she was a Baptist. At the time, there was no talk about the reunification of families and the Soviet Union wouldn’t have allowed it anyway. So those who left, left knowing that they most likely wouldn’t see their family members ever again; and many of them didn’t.

Families were scattered around the world and large emigrant communities were formed in countries like Sweden, Australia, Canada and the United States. In every single Estonian family there’s someone who’s fled to the West. And there’s someone who was deported to Siberia. Being forced to flee and being deported to Siberian camps are two sides of the same coin; on one side, being forced to leave your home, leave your country, leave the people you loved – and the other, shattered family ties. Nobody did it for fun or adventure. They did it because they had no other choice.

Most of the refugee communities considered it their duty to keep Estonian culture alive in exile. Just like all of the world’s refugees, they wished for their kids to become doctors or lawyers – to find a profession that would be needed when it came time to reclaim independence and rebuild the country. At the same time, no one outside of these communities believed that the Baltic States would ever regain their independence and that the Soviet Union would collapse. At this very moment, those who are fleeing today’s crisis regions are also likely to rebuild their homeland again some day – just like the descendants of the Estonian refugees, who did their part after Estonia regained its independence. Dictatorships never manage to last forever, despite their attempts to convince themselves and the rest of the world that they will.

Being forced to leave your home is something that all Estonians have very strong feelings about, just like those from other nations whose own citizens are living in diaspora. That’s why news about Syrian or Ukrainian refugees is so very painful, and why it pains me to see how little we remember about our own past. That’s the only explanation for the hatred, the rise of extreme right wing sentiments and the populist arguments that people are ready to swallow despite the lack of truth in any of them.

The current refugee crisis is not the worst one we’ve ever encountered. Only 6 percent of the refugees of the world are actually in Europe. And consider our recent history: After the revolutions in Russia, 1.4 million people came to Europe. After World War II, there were 65 – 70 million people who had lost their homes, and the Balkan wars forced 2.3 million people to leave their homes. Even Finland, known to have few foreigners, has had lots of refugees in the past. In the 1920s and 1930s, Finland was a very popular transit country and we had more refugees than any other Nordic country. Most of them might’ve stayed, had it not been for the economic recession that hit the country and forced them to continue on their journeys.

After World War II started, Finland became a transit country for Estonian refugees. They were afraid of being extradited to the Soviet Union. Even Sweden returned many Estonians to the Soviets, so their fears weren’t baseless. The deportation of those Estonians continues to weigh on the Swedish conscience and they have repeatedly expressed their official and unofficial regret for having done so.

In Finland, we acted upon the regrets of our past decisions back in the 1990s, when president Mauno Koivisto launched a repatriation program for Ingrian Finns living in the former Soviet territories. They had come to Western Finland as internal refugees, but after the Moscow Armistice in 1944, they were extradited to the Soviet Union and their fate was not a good one: they were not allowed to return to their homes. Due to the length of time they spent in Finland and their exposure to freedom in Finland, they were considered untrustworthy by the Soviet authorities and were deported deeper into the Soviet Union. I am sure that internationally, the Soviet Union was considered a safe country to return to. Just like our immigration office currently believes that the refugees they extradite now can return to their home country safely so long as they choose a different city to live in, and not the one in which they were persecuted. This is logic born out of a democratic state, and in democratic states, decisions are not made following the realities of a non-democratic state.

The way we are now dealing with refugees is something that future generations will not understand.

I have written about the Estonian diaspora, genocide, refugees and deportations. Future authors will write these same stories, but will set them to our times.

Despite all this, no one in Finland defined Finland as an immigration country until the 1990s. We didn’t have public discourse about racism before the 1990s either. After World War II, we had a national mission to unite the nation. All of this has made Finland into a country living in a lie: we’ve always had refugees living amongst us, but we pretended like we didn’t. We also had 400 000 internal refugees originally from Karelia, which Finland lost to the Soviet Union. They were called “evacuees” and not internal refugees, which hurt some of them badly because they did not leave their home of their own free will. Ever since the latest refugee crisis hit, the discussion about Finland’s own nternal refugees has heated up.

ceded to the Soviet Union in 1940. Photo: Wikimedia years.

Some of them and their descendants feel great empathy towards the new refugees, but some feel insulted by being defined as such. They say it’s a totally different matter, and they seem to perceive some insult in the word “refugee”; as something to be ashamed of. Old wounds have been torn open again: those fleeing Karelia weren’t welcomed by Finns with open arms. They were called “Russians” and “infidel dogs”, because many of them were Orthodox and Finland was a very Lutheran country. Finland still is, in fact, a Lutheran country – having Orthodox newcomers didn’t make Finland an Orthodox one. That’s why I find it so strange today that many Finns have a fear that Finland might be taken over by Islam, just because we have a small number of Muslim refugees. Estonia was occupied by an atheist empire, but that didn’t make Estonia an atheist country in the end. Nor did Estonia become an Orthodox one, even though many of the Russians coming to the country were Orthodox by faith, and that the total number of them was huge – the population of Tallinn, for example, doubled in just a few In Estonia, the heated debates about refugees has a different background. After the Soviet Union occupied the country, Estonians had to endure years of state imposed Russification.

When the occupation started, hundreds of thousands of Russians were relocated into the country, of just one million people, making -among other things- the matter of housing very problematic. The newcomers became A-class citizens while the Estonians formed the lower class, just at a time when Soviet propaganda slogans loudly boasted about the equality of all people. I still remember, how taxi drivers – most of them Russians – didn’t let you into their cars if you spoke Estonian. They pretended you didn’t exist. So did retail sales personnel – and most of the shop assistants were Russians. In a country where there was a shortage of everything, a position in a shop was a very privileged one. It was blatant racism, but it wasn’t called that – officially racism didn’t exist in the Soviet Union. If the word racism was used in the Soviet language, it was only to taint the United States and other capitalist countries; it was considered a capitalist problem. That’s why the racism discourse, the way we understand it in the West, didn’t exist until recently, and is progressing with baby steps.

The social memory of immigration is totally different in Estonia and other Eastern European countries than in the Western countries. In these territories, people are used to only one kind of immigrant: the occupiers. The reluctance to take in new refugees is based in a complicated mix of history, economics and the fact that nobody actually cared about the persecution the indigenous people had to deal with in occupied territories. Therefore, Western talk about human rights sounds very hypocritical to the ears of the Central and Eastern European.

So the question is, how hypocritical are we going to look in the eyes of future generations? In our own countries or in the Middle-East? Will the next generation ask the same questions we asked about Hitler and the Holocaust: “how could you let that happen?”. Is that how we want to be remembered? And when they do ask those questions, they will be facing the same problems we are facing right now. For instance, in Eastern European countries, it’s very difficult to make people believe in equality and, let’s say, women’s rights. The Soviet Union tainted those words with their propaganda and brainwashing, but that’s not the only reason: it’s difficult, because we have not treated Eastern Europeans like equals. For political reasons we didn’t care about concentration camps in the Soviet Union. So why should they trust our talk about human rights now?

There’s only one difference we have with the past: due to freely streaming information and news, we cannot pretend we don’t know what’s going on.

Text of a speech Sofi Oksanen delivered in Stavanger, Norway, September 2016.

Copyright © 2015 UpNorth.eu

Sofi Oksanen Film från när sovjettrupper lämnar Tallinn 1991

Sofi Oksanen talar om varför människor i väst inte förstår historien i öst.

Oksanens böcker

Norma När håret blir handelsvara

HBL. Publicerad: 25.09.2015

Den eskalerande handeln med hår är ett tema i Sofi Oksanens nya roman. Surrogatmödrar är ett annat.

Nej, Sofi Oksanens pampiga hårman är inte begärlig för den som vill bli rik på andras hår.

– Mitt löshår är gjort av plast och sådant hår vill ingen ha, säger Oksanen och ser lätt road ut.

Andras hår är däremot numera eftertraktat. I väst förlänger allt fler kvinnor sitt hår, utan att grubbla över varifrån det hår deras frisörer förser dem med kommer.

– Det finaste och dyraste håret kommer från Ryssland och Ukraina, säger Sofi Oksanen och berättar om det öde en rysk fånge med långt och tjockt hår kan råka ut för.

– Det händer att fångvaktarna klipper av dem håret och därefter säljer det vidare.

Hår är handelsvara också på andra håll i världen. I Indien finns hinduer som offrar sitt hår för sin tro. Vad de inte vet är att templen säljer håret vidare och blir stormrika. I Venezuela har myndigheterna i vissa städer uppmanat kvinnor med vackert och tjockt hår att dölja det, för sitt eget bästa.

– Det finns vittnesmål om kvinnor som blivit överfallna i köpcentrum, som hållits fast med våld och som snaggats, säger Sofi Oksanen

– En del kvinnor klipper frivilligt av sig håret för att till exempel kunna köpa skolböcker åt sina barn. Men att ofrivilligt bli klippt är kränkande.

Allt oftare landar numera det hår som småningom ska ingå i den internationella skönhetsindustrin, i Kina. Här finns stora fabriker specialiserade på att tvätta, färga, blondera och permanenta hår så att det blir så tjockt och glänsande, och dyrt, som möjligt.

Ett fint extra hår kan kosta mellan hundra och tusen dollar.

Den som kontrollerar hår, kontrollerar också kvinnor, står det i Sofi Oksanens nya roman Norma. Romanen, som är hennes femte, utspelar sig till stor del på en damfrisering i Berghäll.

– En damfrisering är både ett offentlig och ett privat rum, kommenterar Oksanen.

Norma är en thriller med övernaturliga inslag. Romanens hjältinna Norma Ross har nämligen en egenskap som får alla dem som dreglar över ett nytt hår att gnugga händerna, hennes hår växer med över en meter i dygnet.

Egentligen skulle det som nu är en roman bli en novell men Oksanen upptäckte att hon hade mer på hjärtat än hon hade tänkt sig. Resultatet blev en kriminalroman utgående från etiska och moraliska problem inom skönhets- och läkemedelsindustrin.

– Den tekniska utvecklingen vad gäller frågor som hårförlängning och surrogatmödrar har varit snabbare än lagstiftningen har mäktat med, påpekar Oksanen.

Sofi Oksanens fjärde roman ges ut den 31 augusti 2012. Boken har på finska titeln Kun kyyhkyset katosivat, (När duvorna tystnade). Den utspelar sig i Tallinn mellan 1930- och 1960-talen. Berättelsen handlar om vilka alternativen var för människorna, lojalitet och otrohet, om anpassning i ett förlorat land, vars öde skulle förbli under inflytande av ockupanterna. I Tallinn ges boken ut dagen innan, samtidigt som filmen Utrensning får premiär i Tallinn.

Förintelsen har fått stor uppmärksamhet medan Sovjets större förbrytelser förringas. Den röda terrorn accelererade från 1937 och krävde mer liv än förintelsen. Det är ju segraren som skriver historien och då blir mord i kommunismens namn rumsrena medan förlorarna tyskarnas dåd blir noggrant rannsakade.

Sovjet/Ryssland och kommunismen har ännu inte erkänt sina dåd utan dagens ledare i Ryssland fortsätter förneka det uppenbara. Redan innan Sofi Oksanen givit ut sin bok Utrensning 2008/10 som beskriver det Sovjetiska förtrycket i Estland, kom det protester från Ryssland med motivering att boken var antirysk.

Sofi Oksanen anser att hon i sina romaner talar om den verkliga historien tolkad utifrån människornas upplevelse. De Baltiska staterna utsattes för tre ockupationer som av segrarna förklarats som rättmätiga. För de Baltiska staterna var den uppenbara frågan 1939 hur 6 miljoner människor kunde hota de 188 miljonerna i det kommunistiska sovjet?

Den alt för länge och även bevisligen gällande officiella Sovjetisk/Ryska segerhistorien har fått gälla. Det kan vara orsaken till att de grymheter som utfördes under Stalin och hela Sovjet-tiden förblivit dolda en granskning. Segrarens historieskrivningen kan vara en viktig grund till varför människor i väst inte förstår historien i öst.

Särskilt kan påminnas om när Sveriges utrikesminister Sten Andersson (S) visade på en betydande brist på historiekunskap när han i Tallinn 1991 gjorde ett skandalöst uttalande då han förnekade att Estland var ockuperat. Lyckligtvis återfick Estland, efter tre ockupationer, sin självständighet efter 52 år av ockupation den 21 augusti 1991.

Taas raamat lähiajaloost (Eesti)

„Kui tuvid kadusid” on Oksase kolmas romaan sarjast „Kvartett”, mis käsitleb Euroopa lähiajalugu ja lõhenemist. Nagu sarja nimigi viitab, kavatseb Oksanen sel teemal kirjutada ka neljanda raamatu. Esimesed kaks olid „Stalini lehmad” (2003) ja Oksasele ülemaailmse tuntuse toonud „Puhastus” (2008).

Kirjastuse sisukokkuvõtte järgi räägib „Kui tuvid kadusid” inimeste ees olevatest valikutest, truudusest ja truudusetusest, kohanemisest ja kohanematusest maal, mille saatus on olnud jääda okupantide võimu alla. Tegevus leiab aset „terrori ja rahu aastatel” 1930-ndatest 1960-ndateni. Uut teost esitletakse 30. augustil Tallinnas Nokia kontserdimajas.

Ett glädjande besked från Svenska Akademien

Författaren Sofi Oksanen som skriver på finska med rötter från Haapsalu, har, som den första finländska kvinnan tilldelats Svenska Akademiens nordiska pris. Priset är värt 350 000 kronor. Finländska författare som tidigare fått priset är Bo Carpelan och Paavo Haavikko.

Oksanen säger att hon är glad, eftersom finska författare sällan uppmärksammas med nordiska kulturpris. På prisutdelningsceremonin i Stockholm den 10 april kommer hon att hålla sitt tal på finska. När när hon gjorde samma sak vid Nordiska rådets litteraturpris (år 2010), orsakade finskan en viss förvirring.

Oksanen har tidigare mottagit ett stort antal utländska litteraturpris och nu var det Sveriges tur att uppmärksamma författaren. När det sker här näst i Sverige kan det vara för att motta ett Nobelpris.

Den finsk-estniska författaren Sofi Oksanens nya roman, den tredje i en trilogi om det ockuperade Estland, Kun kyyhkyset katosivat (När duvorna tystnade) kom ut, var det med en stor PR-tillställning i Tallinn. Huvudpersonen Oksanen, med sin välkända moderna framtoning, med blå slingor i håret, starkt målad och snitsigt klädd, skötte marknadsföringen med bravur. Oksanens roman "När duvorna försvann" publiceras i Sverige, Norge och Danmark i april 2013.

Oksanens Estlanstrilogi består av böckerna Stalinin lehmät (Stalins kossor), mästerverket Puhdistus (Utrensningen) och Kun kyyhkyset katosivat (När duvorna tystnar). Oksanen har med böckerna visat att hon behärskar både Estlands och Finlands moderna historia.

Sofi Oksanens roman Puhdistus (Utrensningen) kom på finska år 2008 och en formidabel succé. Boken är översatt till över 40 språk, har satts upp som teater och opera, samt som film.

Sofi Oksanen behärskar både finska och estniska. Kan som alla finländare även något svenska. Nu håller hon tacktalet på finska. Efter att Sverige och Finland hört ihop under 600 år borde detta vara en helt naturlig sak. Efter att Sverige och Estland hört ihop i 149 år borde även det estniska språket få mer uppskattning i Sverige.

När den finsk-estniska författaren Sofi Oksanens nya roman, den tredje i en trilogi om det ockuperade Estland, Kun kyyhkyset katosivat (När duvorna tystnade) kom ut i höstas, var det med en stor PR-tillställning i Tallinn.

Finsk radio direktsänder tillställningen och hade sedan en lång intervju med författaren.

Den nya romanen är tredje delen i en Estlanstrilogi, som består av Stalinin lehmät (Stalins kossor), mästerverket Puhdistus (Utrensningen) och Kun kyyhkyset katosivat (När duvorna tystnar).

Den nya romanens titel syftar på att när tyskarna ockuperade Estland och huvudstaden Tallinn 1941-44, började de skjuta duvor i parkerna för att steka dem till middag, vilket naturligtvis förvånade alla ester.

Duvan är ju också en känd symbol för det oskuldsfulla (esterna?) och för fred och frihet. Bokens huvudtema handlar om hur människor förtrycks, påverkas, förändras och blir svikna, när de lever under en ockupationsmakt och Estland fick uppleva en kort tysk ockupation 1941-44 och sedan ett långvarigt Sovjetvälde 1944-1991.

När årets Nobelpristagare i litteratur utsågs diskuterades priset och vinnaren i finsk radio. Kritikerna var överens om att varken Finland eller Sverige (Efter Tranströmer) hade någon riktig kandidat till priset.

Många ansåg ändå att Sofi Oksanen var på mycket god väg att bli det, så ytterligare några romaner i klass med Utrensningen och hon skulle vara högaktuell. Dessutom tycks Nobelkommittén ha en viss förkärlek för författare från Östeuropa, med en dramatisk 1900-tals historia att berätta.

I en intervju för något år sedan, efter sina stora framgångar, sa Oksanen lite skämtsamt att hon knappast kommer att nomineras till några nya priser i framtiden. En del kritiker verkar inte riktigt gilla hennes stora popularitet i media och inom ungdomskulturen, vilket gör henne till "en messiansk historisk uppenbarelse" och inte till en vanlig romanförfattare.

Så sant som det är sagt, men gör det henne till en sämre författare? I början av 2013 år kom Kun kyyhkyset katosivat ut på svenska.