On the Current State of Research into Soviet and Nazi Repressions in Estonia / Aigi Rahi

Forskning om sovjetiskt och nazistiskt förtryck i Estland

Orginaltexten är översatt från engelska och något förkortad. Orginalet finns att hämta på http://www.history.ee/register/doc/artikkel_1.html. Där finns även länkar till referenserna.

Den aktuella situationen för forskningen om det sovjetiska och nazistiska förtrycket i Estland

Aigi Rahi

Under 1940-talet drabbades , de baltiska staterna av tre ockupationer och ett förödande krig. Dessa händelser ledde till den allvarligaste förluster av befolkningen det århundradet. Den första sovjetiska ockupationen 1940-41 följdes av 1941-44/45 av den tyska ockupationen. I 1944/45 återvände de sovjetiska styrkorna och åter-ockuperade länderna. Den första sovjetiska ockupationen fört med sig arresteringar, deportationer, avrättningar och andra former av förtryck. Den tyska ockupationen förintade nästan helt den judiska och zigenska befolkningen samt motståndare till den nazistiska regimen. Andra världskriget medförde olaglig mobilisering till de både främmande ockupationsarméerna. Den andra sovjetiska ockupationen fortsatte det som påbörjades 1940-41. Politiskt, ekonomiskt, socialt och kulturellt omorganisationer åtföljdes av förtryck: gripanden, deporteringar, långa fängelsestraff och avrättningar var tänkt att befria de baltiska samhällena från de så kallade anti-sovjetiska elementen. Psykiskt och fysiskt våld var legalt.

Sovjetiska förtrycket var inte en olycklig serie händelser. Det var utbrett genom missbruk av individer och familjer, avsiktligt sanktionerat av sovjetsystemet som helhet. Förtrycket har en viktig plats i den politiska och ekonomiska historien, liksom i de demografiska, sociologiska, kulturella och etniska förhållandena. Denna studie är inriktad på det aktuella läget i forskningen om Estland.

Aktuell forskning

Fram till 1980-talet handlade de flesta beskrivningar av det sovjetiska förtrycket 1930-talet. Förtrycket mot de baltiska länderna från 1940-talet togs huvudsakligen upp av forskare som utvandrat. [1]

Under andra hälften av 1980-talet, tillsammans med Mikhail Gorbachev politik av perestrojka och glasnost uppstod i den estniska pressen temat det sovjetiska förtrycket. Från 1986 har fakta offentligorts som tidigare var "vita fläckar". Samtidigt skedde viktiga sociala förändringar med en nationell rörelse "Skydd av det nationella kulturarvet". Början var protesten mot fosfat brytningen och frågor om överlevnaden av den estniska nationen och språket. Förryskningen med dess problem togs upp allt mer och allt djärvare.

Den 14 juni 1987 kommenterade en "Helsingfors" 86 "grupp i Riga, Lettland, offren för 1941 på Liberty Memorial. Den 23 augusti, samlades människor i Hirvepark (Hjortparken) i Tallinn, Estland, för att protestera mot historiska orättvisor. Gravar av fallna i Oavhängighetskriget 1918-19 började vårdas och minnesmärken restaureras. Brott begångna av den sovjetiska makten blev öppet diskuterade.

Eftersom en stor del av befolkningen hade lidit förluster på grund av sovjetiska massdeportationerna i 1941 och 1949 blev detta tema aktuellt. Historikern Evald Laasi var först med att insistera på behovet av att studera problemet med deportationerna i estniska pressen. I slutet av november 1987 kom hans artikel "Ifyllning av vissa luckor" att offentliggjordes i kulturtidningen Sirp ja Vasar (Skäran och Hammaren). Där avslöjas sifferuppgifter om antalet som 1941 och 1949 deporterades. Det redogjordes även för hur många estländare som hade deltog i andra världskriget och i det därpå följande gerillakrig i "Skogsbröderna". [2]

Sedan 1987 har en betydande forskning skett i material som under lång tid varit hemligt. Allmänheten har informerats om vad esterna fått utstå under ockupationstiden.

Den första etappen av forskning försökt att uppskatta omfattningen av förtrycket: hur många människor som var förtryckta och av vem. Genom att dessa frågor nu har fått mer eller mindre kompletta svar har de publicerats. Politiska arresteringar i Estland [4] är en betydande del av materialet.

Efter det historiska mötet i Högsta sovjet i ESSR den 12 november 1989 som förklarade 1940 åtgärder av Sovjetunionen en aggression mot Estland och Estland: s införlivande i Sovjetunionen ogiltigt gavs ett uppdrag till estniska Vetenskapsakademien för att bilda en kommitté bestående av forskare och akademiker för att undersöka om det skulle var möjligt att uppskatta alla de skador som gjorts i Republiken Estland av Sovjetunionen. Den 21 februari 1990 lade kommittén fram sin rapport. Senare publicerad 1991 på engelska under titeln världskriget och sovjetiska ockupationen i Estland: en skade rapport. [5]

Arbetsgruppen under ledning av Arvo Kuddo, utredde befolkningens förluster som i första hand bygger på Evald Laasi forskning. Sammanlagt hittades över 200.000 personer som dödades i strid och i fängelser, som försvunnit och deporteras, som rymt med den tyska armén och som flyktingar från Estland på andra håll. Med andra ord, mer än en femtedel av befolkningen före kriget förlorades.

En månad senare, i december 1989 hade estniska Folk Fronten och Ministry of Economic Affairs bildat en arbetsgrupp för att utarbeta an sammanställning av Estland och Sovjetunionen. Boken analyserar de ekonomiska och kommersiella relationer. Sedan kom 1990 en publikation om social utveckling i Estland från 1930-talet till 1980-talet. [6] Arbetsgrupp som forskade om befolkningens förluster leddes av professor Herbert Ligi från Tartu universitet, som tagit initiativ att sammanställa listor över de som omkom i sovjetiska fängelser och hårda arbetsläger samt deporterades i mars 1949 . Arbetet med dessa kategorier av förtryckta har fortsatt av ordförande i Arkiv Studier vid Universitetet i Tartu.

Den 17 juni 1993, Riigikogu (estniska parlamentet), inrättades den nationella kommittén för undersökning av den repressiva politiken yrkesnomenklaturen och det slutliga målet är "att ge i form av en vit bok på en vetenskapligt underbyggd rapport om alla skador och förluster som den estniska nationen har åsamkats till följd av yrkesreglering ". Det uppskattades att direkt befolkningen förluster uppgick till 196.000 personer eller 17,5% av de före kriget befolkningen. [7]

Den 22 november 1996 bildades ett centrum för forskning om den sovjetiska perioden S-Keskus, (S-centrum). Det lagstadgade målet för S-Keskus är att aktivera, samordna och fördjupa forskningen kring den sovjetiska perioden i Estland. Materialen i presentationer möten och seminarier i S-Keskus publicerats som separata utgåvor av dokument. [8] Den nuvarande forskning fokuserar på genomförandet och förverkligandet av forskningsprojektet "estniska militära och säkerhetspolitik-politisk historia under 1939-1956".

Den 2 oktober 1998 när presidenten i republiken Estland sammankallade den estniska internationell kommission för att utreda de brott mot mänskligheten, i syfte att förbereda en autentisk rapport om förtrycket mot medborgare i republiken Estland eller i Estland genom ockupationen myndigheter i Sovjetunionen och Tyskland. [9] Under 2001 lade kommissionen fram sin första rapport som omfattar perioden med den tyska ockupationen.

De deporterade

Störst vikt har lagts på forskning kring olika deportationerna och det massiva förtryck som drabbade tusentals familjer. Deporteringen av den infödda befolkningen i de baltiska länderna till avlägsna delar av Sovjetunionen inleddes av sovjetiska repressiva organ omedelbart efter införlivandet till Sovjetunionen 1940 och fortsatte fram till slutet av 1950-talet.

Forskning började med att ta reda på hur många som deporterades. Den första stora utvisning, som berörde alla i Estland ägde rum under sommaren 1941. Det var en del av stora sovjetiska deportationerna i alla nyligen infogade områden. Den 22 maj genomfördes deporteringen i västra Ukraina, den 12-13 juni i Moldavien, den 14 juni i Estland, Lettland, Litauen, den den 19-20 juni i västra Vitryssland, den 1-3 juli på estniska öarna.

Listor över de som i juni 1941 deporterades hade sammanställts av professor Vello Salo och publicerats av EMIGRANT estniska romersk-katolska tidskriften Maarjamaa 1989. [11] Listan innehöll namnen på 9632 deporterade som varit registrerade på den första listan över de Zentralstelle zur Erfassung der Verschleppten Esten (ZEV = Centrum för att registrera de deporterades ester), den så kallade Lista Helsingfors. ZEV bildades under tyska ockupationen 1941-1943 med det huvudsakliga syftet med att samla in uppgifter om dem som förs till Sovjetunionen och mördats. Ett upprop publicerades i tidningarna för att registrera alla personer som hade arresterats, deporterades, mobiliseras, skickas till Sovjetunionen i egenskap av att vara i aktiv tjänst eller i tjänsten, antingen dödats eller saknas efter 21 juni 1940.

Senare har en förteckningar över de deporterade publicerades både i Päevaleht och läns tidningar i början av 1990-talet. Under 1993 kom en förbättrad och kompletterad version av den ursprungliga listan av deporterade 1941 att offentliggöras. Den innehöll också namnen på 439 judiska medborgare samt uppgifter om militärer (243 personer) av de estniska 22 Territoriell Corps som blivit bortförda av Sovjet den 14-16 juni 1941. [12]

Siffrorna för juni deporterade har omväxlande varit uppskattningsvis 10157, [14] 10205 [15] eller 11000 [16] personer.

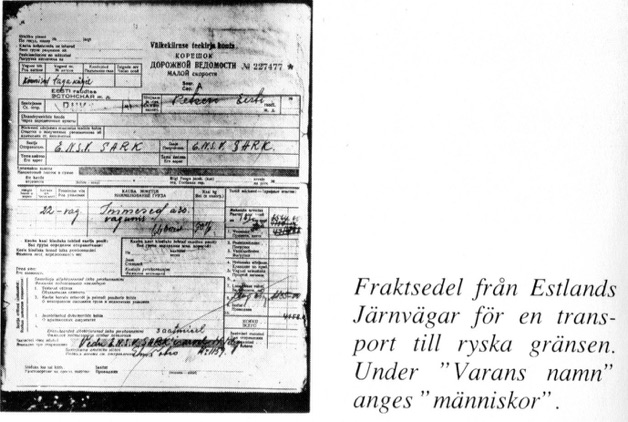

Sista boken innehåller namnen på de som i mars 1949 deporterades. Offer för den mest omfattande utvisning i de baltiska länderna publicerades på 50 åminnelse årsdagen av utvisning på initiativ av den estniska byrån för registrering av den förtryckta. [17] En detaljerad analys av de förteckningar över deporterade från länet i Tartu, då det största länet i Estland, gör det möjligt att konstatera att den 25-28 mars 1949, 20702 personer låstes in boskap vagnar. Material för påtvingat deportationerna från Estland hade förberetts för 31632 personer, men en del av arkivet är obekräftat eller otillgängligt. Frihetsberövande och därefter utvisning av personer finns på listor som sträcker sig fram till 1956. Utöver organiserad deportation finn även jordbrukare som dömts till fängelse för att inte kunna betala 1947/48 jordbruks skatter och därför sänts till Sibirien. [18] Om vi lägger till dessa personer till mars deporterade blir talen definitivt större.

Olika regionala forskningsrapporter och listor har utfärdats för de i mars deporterade. Bäst dokumenterade är listorna för länen i Tartu, Harju, Viljandi, Viru. [19]

I likhet med Estland från slutet av 1980-talet, började både Lettland och Litauen samla in uppgifter om sina utvisade. Särskilda frågor Represeto saraksts, som kompletterar de lettiska arkivens tidning Latvijas arhivi, publicerades data om deporterade 1941 och 1949 samt de som arresterats 1941-1953. [20] Den litauiska publikationen Lietuvos gyventoju genocidas [21] har ännu inte färdiga förteckningar över utvisade 1949. Det litauiska centrumet för forskning kring folkmord och kampen för frihet arbetar nu på åren 1944-1947. Det bör noteras att i Litauen, i motsats till Estland och Lettland, att den första stora deportationen skedde efter kriget och ägde rum i maj 1948.

Från Moskva hävdas att 1949 års utvisning i de tre bifogas stater - Estland, Lettland och Litauen - hade planerats som ett enhetligt kampanj. Det är intressant att göra en statistisk analys av alla listor. Elektroniska databaser har sammanställt i Estland [22] och Lettland. [23] Främst från förteckningar över engångsmeddelanden från ministerierna för inrikesfrågor. Listorna har kompletteras och preciseras under åren. [24] Även om temat är detsamma för historiker i de tre staterna så varierar fortfarande forskningen.

Parallellt har individuella uppgifter från deportationerna undersökts. Ett avgörande genombrott gjordes då tillgången till arkiv som varit sekretess belagda öppnades. Då många direkta källor förstörts söks handlingar även bland indirekta källor. Sökandet i arkivmaterial är utan tvekan ett arbets- och tidskrävande arbete.

I synnerhet den roll som professor i historia Heinrihs Strods från University of Lettland har bör betonas. Han lyckades hitta särskilt värdefulla dokument i ryska staten Krigsarkivet - Material i Sovjetunionens ministeriet för statens säkerhet om hemliga operation "Priboi" 1949, från 25 februari till 23 augusti. Han fick tillgång till materialet i början av 1990-talet då ryska arkiv under en kort tid stod öppna. Allmänheten blev bekant med materialet i 1999, i samband med femtioårsdagen av mars utvisningen 1949. [25]

Under 1999 offentliggöras också i Estland nya uppgifter. Tidskriften Akadeemia utfärdat en fortsättning av handlingar på deportastionen i mars 1949 som bygger på material från läger 17 / 1 i Archives of Central Office of inrikesdepartementet i Estniska SSR, som sammanställts av V. Ohmann och T. Tannberg. [26] Publisering av material som hittats i ryska centrala arkiv samt stat och parti arkiv Siberian oblasts av Ryska federationen är förestående. [27]

Tillgång till ryska arkiven varierar och beror ofta på en slump eller personliga arrangemang. Ett tag förväntade sig få att hitta ytterligare material i Ryssland då de deporterade personalakter förvaras i en filial till den estniska National Archives. Men en expedition till arkiven hos informationscentrum för Institutionen för inrikesfrågor i Tomsk Oblast gav nya bevis. En fullständig rapport om resultaten presenterades av professor i Archival Studies vid Universitetet i Tartu Aadu Must. [28] Allt detta leder till fortsatt forskning kring de deporterades öden. [29]

1949 års utvisning har behandlats i relation till politiken för att avskaffa kulakerna (jordbrukarna). Den sovjetiska jordreform var att avskaffa enskilda jordbruk och ersätta dem med en kollektiv ordning, samtidigt infördes en politisk klass (kulak) att hata. I Lettland har detta undersökts av Janis Riekstinš. [30] Han har också publicerat ett antal dokument på det bredare temat av förtrycket. [31] I Estland finns inget större material med samband till kollektiviseringen. De flesta publikationer hänvisa till material som utfärdats av Myror Ruusmann. [32]

Några mindre deportationer

Utlokaliseringar till Sibirien ägde rum kontinuerligt. Till exempel den 15 augusti 1945 då 407 medborgare av tyskt ursprung deporterades från Estland. [33] Under Sovjetunionen åter annektering 1944 av Estland blev det tidigare området Petseri och området öster om Narva floden införlivat med ryska RFSR. En del av Republiken Lettland införlivades med Pskov oblast. Deportationerna i dessa områden ägde rum i maj 1950 [34] med 1563 (425 familjer), ester och letter. Medlemmar i förbjudna religiösa sekter, 259 Jehovas vittnen, deporterades 1951. [35]

Skogsbröder

Skogsbröderna har rönt uppmärksamhet både i samband med deporteringar och som ett självständigt ämne. Väpnade motståndet mot Sovjetunionens ockupation var ett försök att återställa republiken Estland vid tillbakadragandet av tyska och av sovjetiska ockupations styrkor. Sovjetiska myndigheter hade en klar uppfattning om de politiska målen för Skogsbrödernas kamp. Arresteringar som startade tillsammans med re-annektering av Estland av män söka skydd i skogarna. De som varit med i Självförsvars organisationen och i den tyska armén var de första att arresterades. Således pågick ett krig i de baltiska länderna i flera år efter det officiella slutet av andra världskriget.

I början av 1947, dvs inom två år efter slutet på andra världskriget beräknar myndigheterna att 5868 väpnade "banditer" hade eliminerats. I november 1947 har antalet personer som antingen dödats eller gripits ökat till 8468. Antalet personer som hade blivit "legaliserade" uppges till 6600. [36]

Antalet Skogsbröder skulle ha nått upp till 16000 enligt Mart Laar: s uppskattning. I Skogsbrödra rörelsen kan om alla som under efterkrigstiden gömde sig under en kortare eller längre tid deras antal öka till över 30.000. [37] Uppgifter visa att ca 8000 arresterades Skogsbröder omkring 4000 dödades. [38] Baserat på råmaterial av Eerik Kross "kommande databas" Pro Patria II " kan antalet Skogsbröder som försvunnit vara upp till sex eller sju tusen. För närvarande innehåller databasen c. 2.000 namn. [39]

De arkiverade material som använts vid sammanställningen av listan kommer främst från KGB arkivens bestånd 131 (särskilda upplysningar) och straffrättsliga filer [40] där direktiv handlingar, Skogsbröders brev och dagböcker finns. Listan är tillgänglig på internet, det innehåller också en lista med alla kända medel-Bolsjevikerna eller mord-agenter i KGB (MGB) i Estniska SSR. [41] Hur framgångsrik eller dålig den statliga säkerhetstjänsten var infiltrerar i Skogsbröderna är inte lätt att säga. Filer över agenter är inte tillgängliga i Estland så all forskning bygger på indirekta källor. De metoder som används av avgörande organ har lämnats av Peeter Väljas. [42]

Grundläggande dokument om deportationerna av Skogsbröder publicerades 1992 av Evald Laasi [43]. I och med förekomsten av nya filer har både spännande och fascinerande fakta upptäckts. [44] Rapporter från sovjetiska myndigheter måste dock behandlas med försiktighet då information ofta är i strid med tidigare forskning kring Skogsbröderna. [45]

En omfattande forskning kring Skogsbrödra rörelser har utförts i Lettland [46] och Litauen. Som resultat av lång forskning har Heinrihs Strods publicerat en samling dokument och material om lettiska Skogsbröder. [47] I Litauen har ett antal samlingar av dokument samt resultat av grundliga undersökningar offentliggjorts. Två välkända historiker Arvydas Anušauskas och Juozas Starkauskas [48] bör nämnas, liksom Genocidas ir rezistencija, en specialiserad tidskrift som beskriver väpnat motstånd och brott mot mänskligheten.

Under 14 månader från den första sovjetiska ockupationen (1940-41) greps ca 8000 personer. Uppskattningarna varierar mellan: 8800, [49] 7926, [50] 7043. [51] Leo Talve har uppskattat antalet gripanden till 8000, varav 98% eller 7840 personer dog. [52] 1950 människor dödades på estniska territoriet. De andra dog under åren 1942/44 i sovjetiska fångläger. [53] Beträffande finna att 500-600 av de män som greps kan ha överlevt, dvs 6-8%. [54] Enligt uppgifter från insamlingen Den estniska folkpartiet gjorde om året för lidandet (1943) hade 1850 människor mördades (235 förblivit oidentifierade). [55] Den preliminära förteckningar över personer som avrättades i Estland i 1940-41 som dömts av domstol var (179 personer) och de avrättade utan rättegång (2199 personer). Uppgifterna publicerades 1996 i The Red Terror, genom M. Laar och J. Tross . [56]

Omedelbart efter Röda armén ankomst och återställande av sovjetiska makten i Estland under hösten 1944 svept över Estland en ny våg av arresteringar. Redan före sin ankomst fanns en lista med namnen på personer som skulle arresteras om de hade stannat kvar i Estland. Som regel sändes offren till hårt arbetsläger i flera år.

Ledaren för den estniska kommunistpartiet (EKP) Nikolai Karotamm rapporterar till ministern för statens säkerhet Boris Kumm att inom en månad att av 8000 anti-sovjetiska personer som var registrerade över 200 arresterades. [57] Under ett år, 1944-1945 greps ca 10000 personer, hälften av dem dog under de första två åren. Genom olika beräkningar, under åren 1944-1953 har mellan 25000-30000 personer sändes till hårt arbete och fångläger, en tredjedel av dem (11000) återvände aldrig hem. [58]

Den första volymen av seriell publikation Politiska arresteringar i Estland 1940 -1988 (§ 58) (1995) innehåller personuppgifter om 20164 arresterade personer som har dömts på grundval av artikel 58 i strafflagen av den ryska SSFR. Databasen har sammanställts på grundval av rehabilitering och personliga filer av dem som greps och som bevarats i arkivet i Estniska SSR åklagarmyndighet och Högsta domstolen. [59] Den andra volymen av publikationen (1998) avslöjar personuppgifter på 15001 arresterade personer samt rättelser av personuppgifter för 2215 personer. Den statistiska analysen baseras på de gemensamma uppgifterna i två volymer (34.620 personer, 1995), visar att 2861 personer fått dödsdomar, antalet döda eller mördade i häktena var 8176 (av 34710, 1998). [60]

Minst 475 personer greps under 1953-1988, 375 av dem i 1953. [61] Under 1953 upphör det aktiva skedet av Skogsbrödernas kamp. Under 1956, efter nedslaget av den ungerska uppror kom många partisaner ut i skogen och det väpnade motstånd ersattes av civilt motstånd. I linje med formen av motstånd kan det estniska motståndet (1941-1991) delas in i fem perioder. Perioden för 1955-1985 har undersökts av Viktor Niitsoo. [62]

Frigöranden

Kriget som bröt ut mellan Sovjetunionen och Tyskland under 1941 förde till mobilisering i Röda armén och evakueringen. De flesta författare uppskatta antalet mobiliserade män på cirka 33000. Baserat på S. Larin data har 50000 män mobiliserats i röda armén under sommaren 1941, varav endast 32187 tjänstgör Estland.

I början av sommaren 1941 tjänstgör ca 5500-5600 män (i 22 Territoriell Corps), bildas på grundval av den tidigare estniska armén. Genom att många tjänstemän som har tjänstgjort i den estniska republiken, hade arresterats, skjutits eller deporterades till Sovjetunionen kom i juli 1941 endast cirka 4500 män att tjänstgöra i den 22: a Territoriell Corps i Porkhov (Pskov oblast, Ryssland) ett område taget av den tyska sidan. I augusti 1941 upplöstes kårens och männen sändes till hemmafronten. P. Larin hävdar att 3543 soldater från Estland var kvar i den sovjetiska armén efter detta datum. Estländare som mobiliseras i den sovjetiska armén betraktades som opålitliga både på grund av deras nationalitet och sociala och andra skäl. Antalet soldater som omkom i arbetsbataljoner har uppskattats till 12000, men antalet har inte bekräftats av arkivhandlingar. Uppgifterna om estniska soldater i arbetet bataljoner i 1941-1942 offentliggjordes av U. Usai.

Dessa skickas till fronten och lider stora förluster. En gruppmötte slutet på Velikije Luki (12 december 1942-26 januari 1943). En förteckning över soldaterna i 8:e estniska Skytte Kåren som dödades, dog av sår eller förklarades som saknad (6474 män, vilka under 2400 var estniska födda) har publicerats i boken Velikije Luki in memoriam sammanställs av V. Boikov . Män som togs till fånga eller deserterade till den tyska sidan uppskattads i T. Nõmm är skattning till 1800. Officiellt ansågs de som saknade. Det totala antalet män i Skytte Kåren har angetts till 70000 av T. Nõmm, men det verkar vara en överdrift.

E. Laasi beräknade förlusterna i samband med mobilisering och dödsfall i Röda armén till totalt 9758 personer, 1758 av dem dog medan de transporterades till hemmafronten, 200 dog i 22 Territoriell Corps och 7800 i estniska kåren (1942-1945 ). Enligt "Memento's" Information och historia kommittén, bland 32.100 personer som var mobiliseras, 10% (3210) försvunnit på väg, 40% (12840) dog i arbetets bataljoner, 13% (4170) i strid och 3% (1000) i fängelse. Det uppskattade antalet civila som evakueras till arbete i Ryssland uppskattas till mellan 25000 och 26275, 20% av dem dog på resan.

Tyskt anfall

Den 22 juni 1941 anföll tyska trupper Sovjetunionen. Den 1 juli tog tyskarna Riga, Lettland. Samtidigt började sovjetiska administratörer och militär fly från Estland. Den brända jordens taktik förklaras av Stalin krävde bildandet av "förstörar bataljoner". Omkring 6000 personer som ingick i dessa bataljoner gavs rätt att råna och döda, vilket i sin tur förstärkte den negativa attityden estländare fått av sovjetiska tjänstemän.

Estniska Skog bröder, väpnade grupper av partisaner hade startat sin verksamhet efter 14 juni 1941 deportationer valde att hjälpa den tyska armén. Genom att utnyttja paniken i Röda armen befriar Skogsbröderna södra Estland. Sommaren och kriget 1941 har diskuterats ingående av Herbert Lindmäe.

I reaktion mot den sovjetiska ockupationens politik kom tusentals Skogsbröder att frivilligt stridande i hemvärns enheter i tyskt ockuperade områden. I början av den tyska ockupationen uppgick 50.000 estländare i enheter med den tyska armén och polisen. Siffran var betydligt större än det som planeras av tyskarna. Konturerna i historia i självförsvar enheter i estniska statsarkiv behandlar de viktigaste händelserna börjar med ockupationen av Estland fram till utgången av 1941.

Från sommaren 1942 kom attityden gentemot tyska armén att kraftigt försämrats. Det visar antalet beväringar som flytt till Finland för att slippa mobilisering. Ungefär 3500 av dem var frivilliga i finska armén, och de bildade 200th Infantry Regiment ("finska pojkarna"). I augusti 1944 tvingades cirka 1800 frivilliga återvände till Estland från Finland. För Frihet: Kortfattad Biografier av finska pojkarna (1997) har exakta uppgifter om 3333 "Finska Pojkar", men hur många av de estländare som tjänstgjorde i den finska försvarsmakten kan ha varit högre militärer.

Det är svårt att bedöma exakt hur många av de estländare som kämpade i den tyska armén på grund av brist på arkivmaterial. En bra översikt över de estniska enheter i tyska väpnade styrkorna finns i Toomas Hiio dokument, som publicerades i tidskriften Vikerkaar. I linje med A. Tinits beräkningar, 60000 män helt och hållet mobiliserade. Enligt T. Nõmm kom ca. 70000 ester att tjänstgöra i tyska styrkor, varav 20.000 frivilliga och 50000 värnpliktiga. Den tyska sidans aktiviteter kostade livet för ca: 20.000 estländare.

Det finns olika åsikter om de förluster som estniska civilbefolkningen måste bära under den tyska ockupationen. Enn Sarv, med stöd av "Memento" uppskattningar att antalet lokala offer både de som dödas och de som förintats inte kunde vara högre än 6600, inklusive 929 judar och 243 zigenare. Listan har upprättas av Eugenia Gurin-Loov och har 929 namn. V. Boikov har samlat in personuppgifter om 559 estniska judar och cirka 800 romer som dödades. De uppgifter som återfinns i olika källor är ungefärliga, men alla forskare delar uppfattningen att antalet judar som dödades var mellan 900 och 1000. Nästan 800 personer skickades att arbeta i Tyskland och 4000 människor skickades till fångläger varav cirka 1000 dog.

Dessa uppgifter är absolut inte sista. Dokumentationen återspeglar att avrättningar är ganska stora och kontroversiell. Mer ljus bör ges i ärendet från estniska internationell kommission för att utreda brott mot mänskligheten, som också behandlar öden för människor om kommit till Estland från Litauen, Tjeckoslovakien, Tyskland och Polen. Enligt uppgifter från kommissionens åtta medlemmar i estniska Autonoma Administration dela ansvaret, tillsammans med tyska ockupationen, för brottslig verksamhet mot mänskligheten på estniska territoriet.

När kriget under 1944 nådde Estland uppskattar S. Ise cirka att 35000 soldater från tyska sida blev begravda i Estland, upp till en tredjedel av dem var estländare. Antalet esterna som dödades i strider på estniskt territoriet 1944 anses vara mellan 10000 och 12000 och då räknas inte fångar. Antalet döda i sovjetiska flyganfall uppges till 800. Efter tillbakadragandet av tyska trupper kom ett försök att åter restaurera Estlands självständighet. Detta misslyckades och i september 1944 ockuperade den sovjetiska armén igen fastlandet i Estland.

Under den så kallade Stora Flykten som inleddes i september 1944 då kring 25.000 estländare tros ha nått Sverige. Flyktingar föredrog att försöka nå närliggande Sverige och Finland, men de som flytt i elfte timmen var tvungen att göra det till Tyskland och ca 35000-40000 ester kom dit. Den värsta katastrofen för dem som flyr till Tyskland ägde rum den 22 september 1944 på sjukhusavdelning fartyget Moero. Det hade 2500-3000 personer ombord på fartyget men endast ca 600-700 var räddade. Den 6 oktober 1944 sänktes transport fartyg Nordstern nära Memel (Klaipeda). Ungefär 400-450 estländare försvunnit. E. Ernits har räknat ut att under hösten månader 1944, bland de estniska flyktingar som försökte nå Tyskland ca 1000-1200 personer omkom på Östersjön. Ingen vet hur många flyktingar som försvann till sjöss ombord på båtar som styrs mot Sverige. Det är allmänt uppskattat att av alla flyktingar som anges, ca 10% eller upp till 7000 personer, skulle ha försvunnit. Baserat på de uppgifter som utfärdas den 1 oktober 1946 fanns det totalt 32.219 estländare i DP läger i Tyskland, 16688 i USA zon (inklusive Berlin), 13.698 i den brittiska zonen, 835 i den franska zonen. 998 estländare var i Österrike.

Efter Tysklands kapitulation kom tusentals estländare i östra Tyskland att interneras av sovjetiska styrkor. Det fanns estniska krigsfångar i varje yrke zon. Enligt olika källor togs ca 5000-6000 estländare till fånga av de allierade styrkorna i Tyskland och Tjeckoslovakien. Ungefär 5000-5500 estniska soldater kvar i den sovjetiska zonen. I Estland placerades krigsfångar i läger som satts upp tyskarna och som fanns kvar. Erich Kaup bygger en bra bild av verksamheten i statens säkerhet organ i dessa läger.

Befolkning förluster i Estland bör också omfatta de estniska medborgare med tyskt ursprung som reste till Tyskland som svarar på Hitlers önskan "komma hem". Baserat på 1934 års folkräkning fanns 16346 medborgare med tyskt ursprung i Estland. Under de Umsiedlung, från oktober 1939 till maj 1940 fick cirka 12.660 personer lämnade Estland. Enligt den tyska historikern Jürgen von Hehn var antalet baltiska tyskarna som fanns kvar var 13700, bland dem också 500-1000 estländare (främst som makar). Naturligtvis innebar detta att egendomar blev öde och att många fortfarande saknar ägare. Dessutom inleddes under 1941, under hemvändandet så att 7000-8000 personer lämnade Estland. Under tyskarnas hemresan lämnade ca 10500 personer vänster Lettland.

Boutredningsmän av sovjetiska förtrycket

Undersökningar repressiv politik förutsätter ingående kunskaper om de strukturer och verksamhet av det kommunistiska partiet och dess repressiva organ. Utan tvivel ett Frågan om ett personligt ansvar för de engångsmeddelande ledande tjänstemän. Således, eftersom censuren var lättade i slutet av 1980-talet, en av de viktigaste teman som gällde den roll som den tidigare förste sekreterare i estniska KP Nikolai Karotamm. I sin 1989 utgivare skrifter, både E. Laasi och K. Tammistu benägna att se Karotamm som en marionett, lurade och ersatta av andra, snarare än en arrangör av förtrycket, och de föredrog att lägga hela ansvaret på statens säkerhet organ. H. Ligi i sin tur underströk Karotamm starka personliga samband med utarbetandet och genomförandet av 1949 års utvisning. Senare, många material från KP arkiv bevisat att både Karotamm och KP spelat en ledande roll i 1949 års utvisning.

Hundratals böcker har publicerats om historien bakom den estniska KP, men det är nu dags att ge en objektiv översikt av dem och en början har gjorts. Under 1999, Olaf Kuuli skrev en lång behandling om socialister och kommunister i Estland i 1917-1991. Perioden 1939-1941 har studerats i detalj av professor i historia Jüri Ant från Tartu Universitet. Under åren 1940-1990, Moskva myndigheterna styrde Estniska SSR genom 42 sekreterare och 11 vice sekreterare. Deras biografiska uppgifter som offentliggjordes i ett separat insamling under 2001.

Avslöjandet av det arbete som utförs av enskilda ministrar eller offentliga personer gör det möjligt att få en bättre bild av innehållet i ockupationen politik. Tillsammans med KP apparater, en viktig roll spelade också finansieras av den statliga säkerhets-och inrikesfrågor. Under sovjettiden regel en detaljerad observation av arbetsmiljön mekanismer av dessa institutioner var omöjligt. Genom att nu omfatta hemlighetsmakeri har successivt hävas. I Ryssland flera anmärkningsvärda forskning publikationer har visat sig att IMPEL våra historiker också att gå djupare in i frågan.

I 2001 Valdur Ohmann fullgjort sin MA uppsats på temat "den institutionella utvecklingen av inrikesdepartementet i Estniska SSR och arkivhandlingar (1940-1954)", ett kapitel som också publiceras i tidskriften Ajalooline Ajakiri (Historiska tidning). Problemet med den tidigare sovjetiska institutioner som helhet har dock kommit att uppmärksamma våra forskare först på senare tid, och därför forskningen är bara i inledningsskedet. Dessutom bör forskningen hämmas av otillräckliga och selektiva källor. Därför forskning försöker koncentrera sig på den allmänna politiken i Sovjetunionen som de tillämpas på Estniska SSR.

Tonu Tannberg håller på att slutföra ett stort forskningsprojekt om den politiska situationen i Estniska SSR 1953, som handlar om den interna politiska situationen i Sovjetunionen - Beria nationella och politiska principerna för verksamheten i de baltiska länderna och i Estland, i synnerhet - efter dödsfallet av Stalin. Hans forskning bygger på dokumentation av den estniska KP och inrikesministeriet i Estniska SSR och har delvis varit publicerad i tidskriften konfiskkommissionen.

Ett viktigt bidrag till detta område gjordes av Hilda Sabbo. Hennes dokumentär serie Omöjligt att tiga har blivit fyra böcker. Kompilatorn har använt sig av kopior och utdrag ur Originaldokument i arkiven hos Ryska federationen stämpeln "konfidentiell" eller "TOP SECRET". Många handlingar från arkivet hos OGPU, NKVD och KGB, från material av det centrala i KPSU den politbyrå och deras motsvarigheter i Estniska SSR. Dokumenten som presenteras börjar 1918 och slutar med 1990-talet. Bland de publicerade dokument som man kan stöta på dem som inte är direkt relaterade till Estland ännu spegla den repressiva politiken genomförs överallt i Sovjetunionen.

Sabbo är ett stort arbete, dock finner man olika tvivelaktiga aspekter, som orsakas främst av bristen på noggrannhet. Kompilatorn har samlat mycket olika handlingar i syfte att offentliggöra någonting tillgängliga. De flesta av handlingarna är varken översatta eller kommenterade. Så läsaren krävs av en hel del extra kunskap. Därför skulle det vara lämpligt att tillägga att Mrs Sabbo är inte en historiker. Hon föddes i byn Nya Estland, norra Kaukasus, 1930. Kommer från en förtryckta familj syfte hon har är att ta reda på sanningen om den systematiska förintelsen av den estniska nationen utförd av kommunister.

Dokumenten publiceras i serien Omöjligt att tiga är väl kompletteras med insamling av dokument som utfärdats av den lettiska staten Arkiv Okupacijas varu politika Latvija 1939-1991. Dokumentų krajums. Linjer i jämförelse med Litauen finns i samlingen Lietuvos gyventoju tremimai sovietines okupacines vald˛ ios dokumentuose 1940-1941, 1945-1953 m. Lietuvos istorijas institutas.

Tyngdpunkten i den största uppmärksamheten under senaste decenniet var temat för KGB. En översikt av strukturen och personal från ESSR statens säkerhet och dess funktion som bygger på en analys av tillgängligt material saknas fortfarande. Försök har gjorts, men att beskriva verksamheten som den bedrivs av olika avdelningar.

I slutet av andra världskriget fann Sovjetunionen det svårt att acceptera att tusentals estniska medborgare hade lyckats fly utomlands. Försök gjordes att lirka dem till att återvända till Estland. Rädslan hos flyktingarna att de kan utlämnas var således välgrundad. Propaganda och ideologisk påverkan av de i exil varade fram till upplösningen av Sovjetunionen och var en hörnsten i repatriering politik. Den exil politiken genomförs i sovjetiska Estland och KGB kontakter med baltiska forskning kretsar både hemma och utomlands har analyserats av Indrek Jürjo. Hans bok, som publicerades i 1996, orsakade en livlig diskussion och författaren var tillrättavisas för otillräcklig källa kritik och fokus på en källa.

Några ord om metoder

Forskning om förtrycket förutsätter en komplex analys som gör maximal användning av material från olika institutioner och både skriftlig och muntlig personlig kommunikation. Men eftersom en väsentlig del av den ursprungliga dokumentationen förstörts eller är alltför fragmentariskt och oregelbundna måste forskaren samtidigt arbeta med olika sekundära källor.

En analys av det arbete som gjorts, blir det tydligt att den största delen av forskningen handlar om konkreta händelser och bygger huvudsakligen på materialet i den estniska staten Arkiv och i dess filial arkiv eller tidigare KP arkiv. Att tillgången till ryska arkiven är komplicerad blir tydligt i forskningsresultaten. Omfattande sökningar för att hitta och sålla ut handlingar eller deras kopior i olika arkiv och depositarier är möjlig endast för väl-finansierade forskningsprojekt.

Forskare som har haft möjlighet att analysera händelser och handlingar på olika nivåer har uppnått bäst resultat. Det handlar bland annat om lokal nivå, bland annat län, distrikt, städer, byn råden samt fd republikansk och alla unionens nivåer. Ett stort antal dokument av statligt betydelse (officiellt förpliktas att förstöras) har upptäckts bland lokala arkivhandlingar. Bestämmelser om sekretess av handlingar, återförs till högre organ eller förstöra dem tillämpades olika i länen. Mycket berodde på att lydnad och vård fattas av lokala tjänstemän. Därför kan material i lokala arkiv spelar en viktig roll.

För vissa av de förtryckta (arresterades, deporterades, et al.) Sibirien måste läggas till: platser där dessa personer hade flyttat och var konstant övervakning bibehölls över sina liv. Tyvärr är mycket av dokumentationen fortfarande hemligstämplad. Expeditioner till Sibirien arkiv övertygar att forskning måste ske i olika regioner och arkiv. Trots formellt lika förvaltnings principer om att komplettera, underhåll samt att få tillgång till arkivinspelningar kan olika platser vara helt avvikande. Instruktioner kan ha olika tolkas på olika till lycka för forskare då avvikelser från reglerna att förstöra dokument inträffat.

Med tanke på splittringen av arkiverade material har det samlats in information från ögonvittnen av inträffade händelser stor betydande. Men många händelser tenderar att växa eller tvärtom blivit dystra i efterhand. Från tid till annan, tidigare "hjältar" dyker upp, men vid den tidpunkt då händelsen ägde rum fanns det liten eller ingen heroism inblandade. Därför muntliga källor, traditioner och material i enskilda innehav bör behandlas kritiskt och endast i relation till arkivinspelningar. Jämföra internt material hjälper till att reda ut fel och brister.

Forskning kring olika demografiska, nationella och sociala aspekter som kräver tillgång till representativa statistiska uppgifter. Många siffror publicerade i litteraturen i dag kan bara betraktas som ungefärliga. Med människor ständigt på resande fot lämplig demografisk statistik saknas och avvikelser i uppskattningar kan vara ganska stora, når inte in tiotals men i hundratusentals.

Med utgångspunkt från olika källor, olika enskilda databaser har sammanställts för att få hela bilden av förtrycket. Under år 2000 startas ett projekt "en gemensam databas på estniska Befolkning Förluster" som omfattar alla kategorier av förtryckta. Vidare möjliggör blandning av olika former av förtryck och specifikation av omfattningen av den repressiva politiken mot den estniska befolkningen.

Sammanfattning

Fram till slutet av 1980-talet var vetenskapliga forskningen om sovjetiska repressiva politik komplicerad. Först och främst på grund av bristen på råmaterial och deras strikt sekretess. Handlingar om de baltiska emigranterna var av propagandistisk karaktär. Under det senaste decenniet har många forsknings artiklar, översikter, reminiscensens osv dykt upp i de baltiska staterna.

Det senaste decenniet av forskning om förtrycket kan betraktas som en period av ett sökande efter, återuppbyggnad och preliminär statistisk analys av källor. Kategorier av förtryckta har studerats på olika nivåer och med olika fokus. Därför har estniska, lettiska och litauiska forskare kunnat dra nytta av att utbyta erfarenheter och material.

Både estniska och lettiska forskare har gjort framsteg när det gäller att analysera förteckningar över utvisade i 1949 deportationer. Lettiska och litauiska historiker har grundligt studerat sambandet mellan 1949 utvisning och Skogsbrödra rörelsen. Lettiska forskare har klarlagts den militära aspekten av deporteringen. Estniska forskare har lyckats att intervjua hundratals offer för fånglägren och lägga en mänsklig dimension till forskning. Både lettiska och litauiska kolleger har erkänt framsteg som gjorts av estniska forskare för att finna ut om de vardagliga levnadsvillkoren för estniska utvisade i Sibirien. Jämförelse av handlingar och enskilda filer gör det möjligt att komma närmare till att skapa en fullständig bild om sovjetiska former och metoder för förtryck som genomförts i de baltiska staterna.

Baltiska samarbete har i detta avseende förmodligen fungerat bäst i exil eller vid konferenser i Paris, Stockholm, New York och på andra håll utanför Östersjön. Även vid den tidpunkt då frågan om förtryck var politiskt aktuella hade vi inte några gemensamma strategier. Som tidigare, det bästa exemplet på ett sådant partnerskap är Misiunas-Taagepera bok om de baltiska staterna: åren 1940-1990. Men i förordet till boken påpekas att estniska och litauiska exempel och illustrationer dominerar i boken eftersom "ett av våra svåraste uppgifter var att använda original litteratur på lettiska.

Insamlingen av uppsatserna om den Anti-sovjetiska motståndsrörelsen i Baltikum är en av de senaste försöken av historiker i våra tre länder att skriva på ett gemensamt tema. Förhoppningsvis kommer snart en jämförande studie av ett rikligt källmaterial på ett annat tema att göras. På ett sätt är det ett partnerskap som kan hitta fram sidor på Internet. Således http://vip.latnet.lv/LPRA ger information om brott mot mänskligheten i Lettland, som innehåller viktiga referenser till publikationer av estniska och litauiska forskare.

Summing up

Up to the end of the 1980s any scientific and scholarly research into the Soviet repressive policy was complicated, first of all, due to the lack of source materials and their strict confidentiality. The treatments by the Baltic emigrants were rather propagandistic in nature. During the last decade, numerous research articles, overviews, reminiscences, etc. have appeared in the Baltic States.

The past decade of research into repressions can be regarded as the period of a search for, reconstruction and preliminary statistical analysis of sources. Categories of the repressed have been studied on various levels and with a different focus. Therefore Estonian, as well as Latvian and Lithuanian researchers would benefit from sharing experience and materials.

Thus both Estonian and Latvian scholars have made progress in analysing the lists of the deportees of the 1949 deportations. Latvian and Lithuanian historians have thoroughly studied the relationship between the 1949 deportation and the Forest Brethren's movement. Latvian researchers have elucidated the military aspect of the deportation operation. Estonian researchers have managed to interview hundreds of victims of the deportation, adding a human measure to the research. Both Latvian and Lithuanian colleagues have acknowledged the progress made by Estonian scholars in finding out about everyday living conditions of Estonian deportees in Siberia. Comparison of documents and individual files enables to get closer to creating a full picture about Soviet forms and methods of repression as implemented in the Baltic States.

Baltic partnership in this regard has probably worked best in exile or at conferences in Paris, Stockholm, New York and elsewhere outside the Baltic. Even at the time when the repression issue was politically topical we did not have any considerable joint approaches. As before, the best example of such a partnership is almost a classic two-man Misiunas-Taagepera book Baltic States: The Years of Dependence 1940-1990. However, the Preface to the book points out that Estonian and Lithuanian examples and illustrations predominate in the whole book because "one of our hardest questions was our inability to use original literature in Latvian".

The collection of papers The Anti-Soviet Resistance in the Baltic States is one of the most recent attempts of historians of our three countries to write on a common theme. Hopefully, a comparative study of abundant source material on some other theme will soon be done. In a sense, a partnership may possibly find its way to the pages of the Internet. Thus http://vip.latnet.lv/LPRA yields information about the crimes against humanity in Latvia, containing important references to publications by Estonian and Lithuanian researchers.

© Scandia 2010http://www.tidskriftenscandia.se/

Preoccupied by the Past

The Case of Estonian’s Museum of Occupations

Stuart Burch & Ulf Zander

The nation is born out of the resistance, ideally without external aid, of its nascent citizens against oppression [...] An effective founding struggle should contain memorable massacres, atrocities, assassina- tions and the like, which serve to unite and strengthen resistance and render the resulting victory the more justified and the more fulfilling. They also can provide a focus for a ”remember the x atrocity” historical narrative.1

That a ”foundation struggle mythology” can form a compelling element of national identity is eminently illustrated by the case of Estonia. Its path to independence in 1918 followed by German and Soviet occupation in the Second World War and subsequent incorporation into the Soviet Union is officially presented as a period of continuous struggle, culminating in the resumption of autonomy in 1991. A key institution for narrating Estonia’s particular ”foundation struggle mythology” is the Museum of Occupations – the subject of our article – which opened in Tallinn in 2003. It conforms to an observation made by Rhiannon Mason concerning the nature of national museums. These entities, she argues,

play an important role in articulating, challenging and responding to public perceptions of a nation’s histories, identities, cultures and politics. At the same time, national museums are themselves shaped by the nations within which they are located.2

The privileged role of the museum plus the potency of a ”foundation struggle mythology” accounts for the rise of museums of occupation in Estonia and other Eastern European states since 1989. Their existence – allied with a plethora of analogous monuments and memorial sites – testify to a pervasive

preoccupation with the past – or, more accurately, pasts. For these accounts, as well as being shaped by national parameters, are inherently plural. This is by no means unique to the Baltic States.3 Yet what makes them special is the amount of media attention they have accrued.

One instance of this was the dilemma facing the leaders of the Baltic States as to whether or not they should attend the celebrations scheduled to take place in Moscow in 2005 to mark the 60th anniversary of the end of the Second World War.4 They were acutely aware that, in the case of the Baltic States, the celebration of the defeat of Nazism was tainted by a far more long-lasting period of suffering – namely the occupation of their nations by the Soviet Union. This, however, was utterly at odds with the vociferously expressed view of Russia’s present-day leadership, including the then Russian First Deputy Prime Minister, Sergei Ivanov.5 For them the ”Great Patriotic War” (the Soviet term for the Second World War) is the key to their own ”founding struggle” and ”the resulting victory” was as justified as the so-caled occupation of the states of Eastern Europe that followed the conflict. The memory of the struggle against Nazi Germany is sacred to the Russians and, in the words of Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, any attempt to ”blaspheme this memory, to commit outrages against it, to rewrite history, cannot fail to anger us”.6 They share this interpretation of the past with many of the ethnic Russians that constitute sizeable percentages of the presentday Baltic population.

Definitions of, and identifications with, victims have been high on the agenda all over Europe during the last decades. Estonia could, due to both German and Soviet occupations, rightfully claim victimhood. Yet a factor further complicating this is the pressure placed on the Baltic States to con- form to a Western norm that sees the crimes against humanity perpetrated by Nazi Germany as unparalleled in their orchestrated scale and barbarity. The Baltic States, as new members of the European Union, are compelled to accede to the dissociation from the Holocaust as the European foundation mythology.7 Yet, for many, the necessity to come to terms with their Nazi past is seen as being of far less importance than the need to highlight the injustices of the Sovietera – injustices that did not end until the last decade of the twentieth century. This extends to the argument that complicity with the forces of Nazi Germany can be understood, if not actually excused, as an undesirable consequence of Soviet aggression. Of course, on such terms, the opposite (i.e. complicity with the Soviets to defeat the Nazis) is surely equally true. This scenario, however, is complicated by the fact that the events of the Second World War are inevitably understood in the light of what came afterwards. This has led James Mark to argue persuasively that the various museums of occupation in the Baltic States ”contain” the crimes of fascism in favour of condemning the Soviet regime.8 This version of the past is pursued in order to produce an ”effective founding struggle” that meets the needs of these now autonomous and avowedly ”European” states.

The ”facts” of this history are, then, never given and are always in need of both interpretation and motivation. They are capable of supporting radically different points of view. Therefore, it is not just a case of ”remembering the x atrocity”. Rather it is deciding whether it was an atrocity and whether it merits recalling above y atrocity or z atrocity. Then it is a question of how to present this historical event. In many East European countries, a major task for historians after 1989 has been to discuss not only the atrocities themselves, but also the Soviet tendency to disregard them in official historical accounts right up until the collapse of the Soviet Union. As Andrus Pork has noted, there are a number of both ”direct lies” and ”blank pages” which Baltic historians have since had to contend with.9 Still, the focus in the work of, for instance, the Estonian International Commission for the Investigation of Crimes against Humanity, has been to document what actually happened rather than explicitly analysing Soviet and Estonian uses of history.10

This article is, however, concerned with just such matters: namely the purposes to which history has been put and an analysis of how the past is presented in different contexts. An important forum for doing that is the museum. One particularly noteworthy example is the Okupatsioonide Muuseum in Tallinn, the subject of this article. That museums shape national history and collective memory – thereby justifying the present as well as articulating the past – means that they are both valued and value-laden sites. It is for this reason that as many investigations and interpretations as possible should be made into these institutions, even if the stance adopted is limited to that of an ”outside” observer. Just such a partial perspective characterises this article. We approach our case study from the standpoint of a historian and an art historian brought together by a shared interest in museology and the nature of historical consciousness. Our understanding of the Okupatsioonide Muuseum is reflective of a sizeable proportion of visitors to Tallinn who speak neither Estonian nor Russian. This has had two consequences: firstly a focus on the presentation of the museum in English and, secondly, a heightened awareness of the visual language of the museum as conveyed by its location and layout.

Occupations – Old and New

”First: this is a museum of occupations, not of the occupation.”11 These words were spoken on July 1, 2003 by Estonia’s then Prime Minister, Juhan Parts at the inauguration of Estonia’s Okupatsioonide Muuseum. He was referring to the period from 1940 until 1991, a span of time divided into three occupations of Estonia – once by Germany (1941–44) and twice by the Soviet Union (1940–41 and 1944–91).Its exclusive focus is therefore the twentiethcentury. It does not address the much more distant Swedish” occupation” that lasted from 1561 until 1710. Whilst this has been described affectionately as the ”Happy Swedish time”, this is certainly not the interpretation placed on the course of events narrated by the Okupatsioonide Muuseum.12 Both to symbolise this and to explicitly connect the museum with the ”fight for freedom”, its principal benefactor, Olga Kistler-Ritso, cut through barbed wire at its inauguration in the summer of 2003.

What is frequently – and inaccurately – referred to as ”the Occupation Museum”is then, as Parts emphasised,a museum devoted to multiple occupations. It is also a museum of multiple titles. Its English name varies considerably. The compendium of Estonian Museums compiled by the Estonian Museum Association lists it as the Estonian Occupations’ Museum.13 The website of the museum itself is entitled Museum of Occupations. A leaflet available at the museum in 2007 names it as The Museum of Occupation and of the Fight for Freedom. Meanwhile the blurb on the back of a DVD recounting the history of the institution and on sale in its shop refers to it as the Museum of Recent Occupations (with the inclusion of the word ”recent” obverting the potential question mark over the 1561–1710 period).14

These multiple titles are a particularly clear reminder that ”museums function as palimpsests upon which public histories and national identities are written and rewritten”.15 It also serves to indicate that what the nation ”means” is processual, not fixed and that the past is constantly being reinterpreted and renegotiated in the present.16 Museums, as has already been mentioned, play a significant role in that process. Laurajane Smith, in an article first published in 1993, detected an increasing awareness of the ways in which museum dis- plays ”[provide] the basis from which we in the present construct notions of self and cultural identity”.17

The ”we” referred to by Smith is important. For the ”facts” of history can support diametrically opposed interpretations according to who ”we” are and how ”our” past is construed and displayed. The principal ”we” of the Museum of Occupations is not the Estonian state. It is not, strictly speaking, a national museum. Whilst its very existence in the Estonian capital can and should be construed as an affirmation of official endorsement, the museum is in fact a private initiative that, like our analysis, took shape beyond Estonia’s borders. The private – or, more accurately, personal – nature of the museum was stres- sed by its patron, Lennart Meri, president of Estonia from 1992 until 2001. At its opening he characterised the museum building as the place where ”an Estonian family [had] invested all of its savings”.18 Meri was referring to Dr Olga Kistler-Ritso, an American-Estonian eye-surgeon who had fled

Estonia to ”the refugee camps of Germany” in 1944. Nearly 60 years later, the 83-year-old returned to her homeland to inaugurate the museum which she had reportedly funded to the tune of EEK 35 million.19 The Museum of Occupations therefore represents the tangible culmination of the Kistler-Ritso Foundation, established in the United States in 1998 ”to gather, document and display statements and reminiscences from the Estonian contemporary history”.20 It now achieves this through the auspices of the Museum of Occupations.

That the intended audience for this institution is both local and international was stressed by Tunne Kelam at the opening of the museum. Kelam, one of four board members of the ”Kistler-Ritso Estonian Foundation” expressed the hope that it would provide

younger generations [of Estonians] as well as foreign visitors [...] an understanding of the difficult path of the Estonian people, but also of their unique experience of preserving their spirit, language and culturean experience that we can share with materially better off nations.21

Kelam’s allusion to ”better off nations” provides a partial explanation and justification as to why Estonia’s ostensibly ”official” Museum of Occupations was conceived by a private foundation on which it is still financially dependent. The funding of museums influences how they operate, even if they exude impartiality. This is the case whether support comes in the form of public or private sector funding, corporate sponsorship or personal philanthropy. This, however, only really becomes apparent during moments of controversy. An eloquent example of this was the response to the Smithsonian museum’s decision in 1994 to display the Enola Gay, the B-29 Superfortress bomber that dropped the atom bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. The presentation of this artefact resulted in a heated ”history war”. Sensitivity as to how to exhibit the nation’s past in the United States has only increased in the wake of the attacks of September 11, 2001.22 Less debated but yet just as problematic is the Terror Háza (House of Terror) museum in Budapest. Although it is dedicated to victims of both Nazi and Soviet persecution, only two out of twelve rooms deal with the Arrow Cross and Nazism. Hungarian antisemitism is therefore downplayed. This becomes even more apparent when the House of Terror is compared with the Holocaust Memorial Centre in Budapest.23 It is the former, however, which has attracted most Hungarian visitors because it ”is not a traumatic, commemorative place, but an object of the political uses of the past, whose telos is the maintenance of the representation of the nation of sufferings caused by communism”.24

Sensitivities are also apparent in the recent narration of Estonia’s national history, not least given that there is a palpable lack of consensus over how to interpret the Soviet period that lasted from 1944 until 1991. Non-Estonian visitors to Tallinn would not easily be able to detect such a divergence of opinion from the displays of the Museum of Occupations. It took the riots that erupted on the streets of the Estonian capital in April 2007 to make this shockingly manifest. They were triggered by the relocation of the ”Monument to the Liberators of Tallinn”. This Soviet era commemoration – more frequently referred to as”the Bronze Soldier”– was unveiled on September 22, 1947 to mark the third anniversary of the Red Army’s entry into Tallinn. It is, for a sizeable minority of Estonians, primarily a symbol of ”liberation” from Nazi occupation. For the rest it epitomised the fact that one occupying power (Nazi Germany) had been succeeded by another (the Soviet Union).This was clearly the interpretation favoured by the government in power in Estonia in 2007 and sanctioned by the Museum of Occupations. The decision to resite the monument at the Tallinn Military Cemetery on the outskirts of the capital was an attempt to physically marginalise and symbolically reinterpret it. Its removal from the site in the city centre that it had occupied for sixty years triggered two nights of violence during which one person died. This made it abundantly clear that many of the protestors were well aware of the full import of the statue’s relocationnamely that symbolic meaning resides as much in the site of a monument as it does in the monument itself.

The Power of Place

For architects and monument makers, the power of place has been a reality for centuries. Where to put an official building or a statue has often been a question of the greatest importance since buildings and monuments have always had both practical and legitimating functions. Academics, however, have only comparatively recently begun to study the factors that make up a particular place; what constitutes that place; and why it came into being in the manner it did. In so doing a new awareness of how the past was and is presented to the public has come to the fore. So too have the often intense and intricate negotiation processes that enmesh the design of public spaces and which, once revealed, say so much about ethnicity, class and gender construction in urban landscapes.25 Even more recently, the commercial aspects of place and location, not least as a part of the tourism industry, along with people’s subjective senses of places have also become fields of academic research.26

The proponents of the Museum of Occupations manifest a patent awareness of the power of place when they explained: ”The museum also has an additional function: it fulfils the role of a memorial. A place of remembrance

for those whose graves lie in places we are unaware of. The architects have integrated the memorial into the museum and into the city as such.”27 This was to have special significance following the later relocation of the Bronze Soldier. This is because, at the same time as the statue’s removal, the bodies of twelve unidentified Soviet soldiers were disinterred from their resting place alongside the monument and relocated to the cemetery setting. So, whilst the Museum of Occupations and those it mourned was ”integrated... into the city”, the opposite was done to the Bronze Soldier following its dis-integration from its city centre location.

How then is the Museum of Occupations incorporated into the city and what power is collected in the museum building and its surroundings? Designed by the architects Indrek Peil and Siiri Vallner, the museum is located at Toompea Street 8, at the corner of Toompea Street and Kaarli Boulevard. Toompea is also the name of the castle in Tallinn, which nowadays houses the Parliament (Riigikogu). The route between the castle and the museum is intertwined with symbols of the inter-war period and the new post-1991 era of independence. Near the castle/parliament is a rock bearing the inscription ”20.VIII 1991”,manifesting the moment of liberation from Soviet rule.Closer to the museum are two other recently erected monuments, one representing Johan Pitka (1872–1944) and the other Johannes Orasmaa (1890–1943). Both were high ranking members of the Estonian armed forces. Major General Orasmaa, head of the Home Guard, was arrested by Soviet occupation forces

on July 19, 1940 and subsequently died in May 1943 in a Soviet prison. Rear admiral Pitka was the founder of the Defence League which, as one of the principal forces during the Estonian War of Independence (1918–20), mainly consisted of armoured trains and a naval fleet. He lived long periods in exile but returned to Estonia in 1944, upon which he died in unknown circumstances.28

In its original setting, the Bronze Soldier and the associated unknown soldiers’ graves disturbed the line of symbols of Estonian independence. After its removal there is nothing left to interrupt the straight line of ”freedom” running from the Parliament to the Museum of Occupations and the nearby National Library.The presence of the Museum of Occupations thus explicates the absence of the Bronze Soldier. However, the latter’s physical erasure does not mean that its existence has been forgotten. On the contrary, such is the power of place that it is, arguably, far more ”visible” today than when it stood at Tõnismägi, literally a stone’s throw away from the Museum of Occupations.

Within the twisting concrete and glass form of this building is the ”landscape”of the museum.29 The display is drawn from its holdings of some 15,000 items collected over a period of five years. The curatorial team, acting on the advice of the professor of History, Enn Tarvel, arranged these objects in chronological fashion so as to focus on the three aforementioned periods of occupation (Soviet 1940–41, German 1941–44, Soviet 1944–91). Each period is articulated using filmed interviews and artefacts, both of everyday and mi- litary origin.The idea that Communist Soviet society was free from all class

differences is disavowed at the outset by the juxtaposition of two cars: one a luxury model formerly belonging to a highranking party member; the other, despite being a very small and simple make, was still a pipedream for most Soviet citizens. Another quickly discernable facet of the narrative is the way in which the Museum of Occupations tries to illustrate places that were closely connected to Estonia even if they were geographically distant. Thus a line of prison doors and a similarly long row of suitcases reminds the visitor of the many Estonians who were deported to the Gulag by the Soviet regime. The considerable quantity of suitcases can be read as one of the ways that the displays seek to draw subtle parallels between Nazi and Soviet society and between the Holocaust and the Gulag, not least because exhibitions of suitcases at Auschwitz and elsewhere are a long-standing symbol of the Nazi genocide.

The exhibition is dominated by a model of two locomotives running on parallel tracks. On the face of one is the Soviet star whilst on the other is a Naziswastika. These dramatic features again serve to mark the similarities between the two regimes. In between the trains is a void. This vacuum can be seen as evoking the exposed position Estonia found itself in during the Second World War. The trains fit into a Baltic pattern. Instances of this interpretation are to be found in a number of museums and monuments in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. In, for example, the Occupation Museum in Riga and the Genocide Victims’ Museum in Vilnius, the message is that the Baltic States found themselves caught between a rock and a hard place in the wartime years.30 Similarly, the logotype for the Estonian International Commission for the Investigation of Crimes against Humanity is a visualisation of Estonia’s position at the cross-roads between two, equally bloody dicta- torships – one Nazi, the other Soviet.31 Former Estonian president, Lennart Meri, who was a leading member of this commission, once described Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia as ”identical twins”.32 As we have seen, the current Russian leadership – along with many Baltic citizens of Russian descent – vehemently reject this characterisation of the twentieth century.This angry denial explains their fury at what they perceived as the sacrilegious decision to ”destroy” the Bronze Soldier in April 2007. One of the places they targeted during the ensuing riots was the Museum of Occupations, the windows of which were shattered by missiles thrown by some of the protestors.

Shifting Statues

The recent fate of the Bronze Soldier serves as a pertinent reminder that Estonia, like all other post-communist states, is faced with the difficult question of what to do with its Soviet heritage. Of all the tangible legacies of this era the most poignant is the anachronistic pantheon of commemorative statues and memorials. One solution is to simply destroy them and erase all trace of their presence. Another is to remove the symbol itself and either leave the site blank or replace it with another, more acceptable sign. But the latter strategy results in a further question: what to do with the superfluous monument? One widely adopted solution has been to reframe it through an alternative form of display.The most celebrated example of this is Statue Park, also known as Memento Park, which opened in Budapest in 1993.

Another mode of reframing occurs when a monument is reinterpreted by an additional societal agent – such as an artist or curator. Their actions are frequently informed by the notion of institutional critique – especially the critique of the museum.33 One of the most straightforward yet effective actions in this vein was carried out by the American artist, Michael Asher. His decision to move a statue of George Washington from outside the Art Institute of Chicago to an interior gallery holding eighteenth century artworks, whilst seemingly unremarkable, in fact laid bare the powerful influence exerted by museal displays. He showed that meaning can be varied according to shifting historical and aesthetical criteria.34

A particularly sustained example of the processes of such reframing within the museum was presented at the first hang of Kumu, Estonia’s new national museum of art which opened in Tallinn in 2006. It featured an installation by Villu Jaanisoo (born 1963). Entitled Seagull, it consisted of 52 portrait busts dating from the late nineteenth century until the 1980s.They filled an entire corner of the museum. Indistinct voices could be heard emanating from loudspeakers concealed in the pedestals. The numbered sequence of portraits commenced high up on the wall in the form of a bronze bust of Lenin by Georgi Markelov dating from 1970.

This provides an example of an acceptable way in which to display Soviet heritage in contemporary Estonia: instead of a troublesome historical document it becomes an element of contemporary art. This points to the wider remit of Kumu as a whole. Kumu’s role is to tell the (or rather ”a”) story of Estonian art history. The title of the main exhibition – Difficult Choices – related as much to the problematic position artists found themselves in during the Soviet period as to the difficulties faced by the curators in trying to tell a narrative of Estonian art history from the vantage point of a post-Soviet, EU-affiliated Estonia. Indeed, ”difficult choices” characterises practically every aspect of not just Estonian art history but Estonian history in general – be it the dilemmas its people faced in 1940, 1941 or 1991 as well as in more recent times, such as with the removal of the Bronze Soldier in 2007.

A Sepulchre of (In)Famous Men

Dario Gamboni, in his important study of iconoclasm and vandalism, notes that those Soviet-era monuments that were not destroyed were,”as a last resort”, stored in museums. Their triumphant or ironical display in this context serves as a deliberate form of defacement:

the informal, desultory or absurd presentation – no pedestals, traces of paint, prone position – gave the visitors unmistakeable interpretative and behavioural hints that this was banishment and not promotion, and that the works were there neither to be venerated nor to be admire but rather to be laughed at.35

This would seem to be what has happened at Estonia’s Museum of Occupations. Its basement is filled with Soviet-era sculpture, stripped of their elevating pedestals. But the impression it creates is very far from amusing. James Mark in his account of Estonia’s Museum of Occupations observed that the architecture is characterised by large windows which allow in natural light.36 This makes the contrast between the main gallery and the basement particularly stark. This subterranean space is very dark. Low light levels in museums are usually implemented in order to conserve sensitive objects from light pollution. This is not the case here. Rather, the murky conditions are for interpretative purposes, contributing as they do to the oppressive atmosphere. There is no amusement here.

The place is more akin to a storeroom than a gallery.This is exacerbated by the exposed metal pipes and numbered, yellow-framed metal cages that line this industrial-looking space. The visitor is not informed what these things are for. Equally mysterious and unsettling are a series of locked doors. In this context the signs pointing towards the emergency exit take on a strangely urgent feel, not least because the display includes two prison doors leaning up against the right-hand wall. One of these is reproduced on the homepage of the museum: the visitor clicks the prison door to virtually enter this prison of the past.37

In the midst of this sepulchre are the sculptures.38 These are either positioned directly on the floor or on a low ”plinth” formed by the architecture of the building. Thisas Gamboni noted – underscores the anti-heroic nature of the works. They have literally been taken down from their pedestals.The nature of some of these missing plinths is discernible from two laminated newspaper cuttings pinned to the wall. They serve as interpretative panels for the two principal objects: two over-life-size statues. Even to non-Estonian speaking visitors it is clear that, rather than reporting the removal of the monuments, the newspaper articles date instead from the time of their inauguration.They show the statues in their original settings. This emphasises how far they have travelled: from being foci of attention in central locations they are now marginalised in a dark basement. The symbolic and interpretative consequences of this shift help explain why the decision to move the Bronze Soldier was so controversial. The latter now resides, as we have noted, in a military cemetery on the periphery of the city. It has not been destroyed. It has instead been reclassified, just like the statue of George Washington following Michael Asher’s intervention or, even more forcefully, the sculptures in the basement of the Museum of Occupations. What were once ”living” monuments have now become ”dead” memorials.

The decision to pair the two statues that are currently in the basement of the museum was fitting, not least because they were inaugurated within a year of one another. On the right is Mikhail Ivanovich Kalinin (1875–1946), the nominal Head of State of the USSR. His statue was erected at Tallinn’s Field of Towers in 1950. The sculpture which now stands to his right was erected at Harjumägi in 1951. It commemorates Viktor Kingissepp (1888–1922), ”one of the leading figures among Estonia’s communists. He operated secretly in Tallinn... [and] was arrested and executed by a firing squad after being tried by a military court for espionage”.39 Kingissepp thus died a traitor in independent interwar Estonia, was heralded as a hero in Soviet Estonia and is now disparaged once more.40

The statue of Kingissepp has therefore had the exact opposite trajectory to the aforementioned commemorations of Pitka and Orasmaa. It testifies to the mutability of history and of commemorative monuments. Indeed, the ravages of time are written on the bronze bodies of both Kingissepp and Kalinin. The former is depicted as an orator. He gesticulates evocatively with one hand, whilst the other clutches a sheaf of rolled papers. This is meant to amplify his imaginary words. But his oratory is mute. If he ”speaks” at all it is to a subterranean wall. His gesticulating fingers are all missing. Kalinin meanwhile has lost an entire hand. These disabled figures stand next to the door leading to the disabled toilet.

Above the statues is a metal grill where one can hear and see people walk by in the galleries above.This accentuates the subterranean aspect and sense that these figures are entombed here. One character that could not be so inhumed is Stalin: his head was apparently too big to fit in (unlike Lenin’s).

Prime Minister Juhan Parts told those that gathered to inaugurate the Museum of Occupations that it should been understood as being about ”the past not the present, consequently the idea of a museum is appropriate”. Yet he went on to aver that it ”is a place where future generations can see what once took place. Where they can see that which will never be repeated.”This is why the statues are deemed worthy of preservation.They need to be literally contained so that they can safely recall something deeply (un)desirable whilst simultaneously reassuring the visitor that the terror is now over. Yet in so doing there is an anxiety that unwelcome interpretations might somehow leak out. The sculptures might be entombed in this space, but their current position seems somehow provisional. Perhaps one day they will be reinstated in their previous locations? With this in mind it is clear that the museum is serving a moral and political function – a warning from history.

All commemorative monuments deal with time. But in this setting time is literally meant to stand still. Between the figures of Kingissepp and Kalinin is a clock. The hands point perpetually to just after 8 o’clock. Why? Is it in the morning or the evening? In this temporal void the active component is provided by the visitor. Aside from looking at the sculptures, the visitors’ activity includes an act of the very basest kind: for between the statues of Kingissepp and Kalinin is the entrance to the toilets. This further denigrates the ”heroes”. Yet in this place where the sacred and profane collide nothing is as straightforward as it first appears. The liminal zone betwixt the gallery space and the toilets is taken up by a massive, circular water feature that resembles something one might expect to find in a temple or some other sacred place. Behind this is a large, mirrored wall. Its reflection makes the visitor very much aware of their presence amidst the statues, drawing attention to their own diminutive size in contrast to the grotesquely proportioned bronze bodies.

Kingissepp, Kalinin and the other individuals commemorated by these sculptures are all male. Yet this overtly masculine pantheon exists in a very feminine space. Whilst the concrete basement of the Museum of Occupations is reminiscent of a bomb shelter or a prison, the walls of the stairway which leads down to it are lined in red velvet-like textile.This weird parody of honour is comparable to a uterus, whilst the opening at the bottom is akin to a womb – complete with embryonic creatures inside.

The latter are reminiscent of some of the other sculpture produced in Estonia during the Sovietera and which are now on display at the abovementioned Kumu art museum. One such is Son of Regiment (1948) by Sarra Bogatkina (1904–90). A young child marches resolutely forward clearly aping the proud, heroic soldiers he has no doubt been encouraged to admire. A metal helmet – perhaps his father’s – balances precariously on his tiny head. Another example is Father and Son (1977) by Ülo Õun (1940–1988). Here a monstrously large child holds hands with a bearded man. In the version at Kumu the latter’s left arm is broken at the elbow.The fragmentary nature of Õun’s figure finds a weird echo in the two standing statues in the basement of the Museum of Occupations. This raises another shared characteristic: namely a monument’s ability (or not) to communicate – something that is similarly picked up on by the murmuring portrait busts of Villu Jaanisoo’s installation Seagull.