Kulturutbyte under KGBs regi VEKSA

Väliseestlastega Kultuurisidemete Arendamise Ühing Föreningen för utveckling av kulturella relationer med utländska estländare.

Kulturutbyte under KGBs regi VEKSA

Väliseestlastega Kultuurisidemete Arendamise Ühing Föreningen för utveckling av kulturella relationer med utländska estländare.

Det hölls åtta VEKSA seminarier. Det sista 1988.

Från det sjunde (på medaljen Vl, det sjätte) seminariet 1987 redovisas här vad som tilldrog sig.

VEKSA bildades 1960 och upplöstes i tysthet 1989-1991.

Veksa: Were exile Estonians its skillful users or being used?

Var exilestländare VEKSAS skickliga användare eller utnyttjades de?

Nov 2, 2012 Estonian Life No. 44 2012

Veksa as a KGB-controlled organization in Estonia was shut down (collapsed?) in Estonia just prior to the country regaining its independence in 1991. Its effectiveness as an extension of the KGB's and the Estonian Communist Party's outreach efforts to the exile community, or its usefulness as a conduit for establishing ties with cultural figures in the captive homeland is still an open issue. In fact the question is also peripherally broached in the ‘estdocs' film festival's opening film “Outside the Sphere”.

Veksa (an acronym for Väliseestlastega kultuurisidemete arendamise ühing – The Union for Developing Cultural Relations with Estonians Abroad) was established in 1960 for “information exchange with and the ideological influence of” Estonians living outside of their homeland. In actuality, for practically all who have researched Veksa's activities, the organization it was a cover (in reality an open secret) for the Estonian State Committee on Security (KGB) for gathering intelligence and foreign political information. In addition it's been widely stated that Veksa's other prime goals were to forge a rift within the solidarity of the Estonian the refugee society, to recruit agents and to assume control over ties nurtured through personal relationships with individuals in the West.

One of its founders was the late Gustav Ernesaks, cultural icon, conductor, composer and universally popular. Named as Estonia's leading post-war author and nominee for the Nobel prize, Jaan Kross, traveled to the West under the auspices of Veksa. In choosing these and many other examples of prominent cultural figures who had affiliations with Veksa, it would be difficult to prove that they knowingly expended any effort in furthering Veksa's actual agenda. Analogously, amongst the individuals in the West with whom “Veksa-sponsored” cultural personalities from Soviet-occupied Estonia made contact and visited, one would rarely identify someone who willingly and consciously advanced Veksa's real program. (More details of this in a following column.)

It has been widely noted that president Lennart Meri as an author and film maker was able to visit the west numerous times through Veksa's sponsorship and in so doing was diligent in submitting mandatory detailed reports of people he had met and events in which he participated. But Hellar Grabbi, in countering ongoing accusations about Meri's complicity with the KGB, points out that Meri deliberately omitted reporting meetings with people such as Ernst Jaakson, the accredited representative in the USA of a non-Soviet Estonia, and others – meetings that were strictly forbidden by the KGB and detrimental to its clandestine operations. Others also insist that since Meri, as a youth spent some pre-war years with his diplomat father living in Paris and Berlin and developed a deeply-rooted western orientation, he needed to constantly visit the West. He therefore found it necessary to comply with the compulsory submission of reports to again gain Veksa's clearance for travel.

This writer (hereafter LL) was allowed access to the Veksa archives and spent some two weeks combing its internal correspondence, memoranda, minutes of meetings, letters from “associates” abroad and other written material. While some of the archival documents were in Russian, the Estonian language dossiers made it unmistakably clear, that at the very least, Veksa was tasked with winning “true” friends in the West, with convincing the west that Estonia enjoys uninhibited cultural independence, that the Soviet system gives Estonians maximum opportunity to pursue its own indigenous cultural opportunities and that the West should not only accept Soviet reality in Estonia but also help in the promotion of its “achievements”. A directly related aim was to convince younger members of the exile community to distance themselves from the ideological stance of the first generation of refugees “stuck in their cold war mentality”. It would now be impossible to evaluate how successful the KGB was in actually recruiting agents through Veksa's contacts. A substantial portion of Estonian KGB documents were destroyed by the KGB itself or transferred to archives in Russia and access to them has always been denied. Except for the rare exception, it is generally felt that recruitment efforts of bona fide KGB operatives in the west through Veksa auspices on the whole failed.

How close was Veksa's relationship with the KGB and how intertwined were Veksa activities with KGB operations? LL had a chance in the 1980's to meet with Imants Lešinskis, the former head of Veksa's sister organization in Soviet-occupied Latvia, who had defected to the USA, opted for a CIA resettlement program, under protection. The question was put to Lešinskis bluntly, “Were you an officer of the KGB?” “Of course! And my former colleague and counterpart in Tallinn, the head of Veksa, Ülo Koit, is also.” (A future segment will detail this.)

As one example of KGB directed activity Lešinskis went on to explain how the Latvian equivalent of Veksa has assisted the KGB in compiling a list, including their backgrounds, of all possible university graduates in the West of Latvian descent. (Shortly after this meeting, Lešinskis claimed he had been a CIA double agent for two decades which the CIA refused to confirm.)

Laas Leivat – Estonian Life No. 40 2012

Nearly all who have studied the relationship between VEKSA (the Union for Developing Relations with Estonian Abroad) and the Soviet intelligence/security services insist that VEKSA was a direct, ‘clandestine' extension of the KGB. The undercover nature of its existence was a farce. It was an open secret as to who actually directed its affairs and who dominated its leadership.

Founded in 1960 its leadership over three decades contained many KGB and KGB-connected personnel. Some specifics: Randar Hiir – VEKSA secretary, KGB major, who participated in the arrest of dissident Enn Tarto and an anti-Soviet youth group in 1956; Lembit Kumm, a KGB officer from 1967 with a variety of operative undercover assignments, mainly with VEKSA; Lembit Koik, VEKSA sport section secretary, a KGB officer since 1956; Felix Meiner, a KGB officer, VEKSA vice-chairman, left for Russia after Estonia's re-establishment of independence. Some researchers have suggested that the KGB position and direct link to KGB headquarters was always one of the two vice-chairmen. The chairmen, if they were veteran KGB officers, were designated as “trustees” (usaldusisik) during their secondment period at VEKSA.

(It must be pointed out that “trustees” had a totally different status as an informant or agent, both of whom give their signatures on a promissory agreement to work for the KGB. Trustees weren't given code-names and they usually headed governmental establishments, were recognized for their achievements and their services and were considered to be much more vital for the KGB than those of ordinary snitches or informants. They were also entrusted with specific operations.)

Ülo Koit was chairman of VEKSA from 1975 to 1985, the most tension-filled period of the ideological cold war. German documents from the time of their occupation of Estonia in 1941-1944 identify Ülo Koit as being a member of the Komsomol, the Communist Youth Organisation. During this time he was also in Russia as a tractor driver and attending an advanced communist party school. In the fall of 1944 he was appointed the technical secretary of the Central Committee of the Estonian Communist Party. At this time he is recruited as an agent of the NKVD (precursor to the KGB). From 1947 to 1949 he was the editor of a local newspaper the ‘Valgamaalane' and starting from 1950 the editor of literature broadcasts on Estonian Radio. At the same time he was titularly vice-chairman of the state TV-Radio committee. In actuality he worked for the KGB foreign intelligence chief directorate. Documents affirm his trips to Finalnd, Czechoslovakia, China etc. His official service in foreign inteligence lasted for 20 years, making 40 trips to foreign countries in 30 years.

Lembit Kumm, a KGB veteran, recommended him as a participant in ‘Rodina's' delegation on a trip to Canada and the USA. (Rodina was the all-Union equivalent of VEKSA, on the board of which Koit sat.) In his recomendation Kumm said: “On comrade Koit's initiative there have been many interesting efforts in attracting Estonians away from the influence of reactionary immigrants and enlightening them about the real Soviet Estonia.” Arnold Green, Estonia's so-called ‘foreign nminister' during the Soviet occupation describes Koit in a letter as a “demanding and principled leader, under whom VEKSA's activities have diversified especially within the community of Estonian immigrants with respect to supplying information and distributing propaganda.”

While his professional life was secretive but still accessible through documents, both Koit's birth in 1925 and death in 1996 were surrounded more by mystery and contradictory facts. Koit himself claimed he was the out-of-wedlock son of author Evald Tammlaan who died during the Nazi occupation in a concentration camp. Rein Kordes (a.k.a. Andrus Roolaht), the foremost author of anti-refugee propaganda, a close associate of Koit and the secretary for culture and higher learning at VEKSA insists that Koit is actually the son of Oskar Koorits, prominent folklorist who escaped to Sweden during the war and who was known as an inveterate Estonian patriot.

He died mysteriously in 1996 in a Latvian river. Though Koit was considered to be a strong swimmer, the official cause of death was drowning. However journalists and others who have researched the circumstances surrounding his death have raised pertinent questions. While a letter he wrote to a friend in Sweden, prior to leaving alone (he was half-blind during the last years of his life) for a supposedly fishing trip to Latvia might have been interpreted as a disguised suicide note, he told the landlord and wife he was going for a walk.

Speculations about a possible suicide or motives for eliminating him have centred on two scenarios. Indrek Jürjo's book “The refugee community and Soviet Estonia” was about to be published. It drew into sharp focus the KGB role in VEKSA and obviously the personnel involved in targetting Estonians in exile. The other reason given for Koit's death is the intimate knowledge he owned about prominent public figures, specifically their co-operation with the KGB. What drives these speculations is the fact that Koit's burial was in December 1997 and various work-related dossiers he was keeping at his daughter-in-law's house burned in a housefire in February 1997.

Laas Leivat – Estonian Life No. 41 2012

It's clear that the leadership and day-to-day management of VEKSA was entrusted to veteran KGB officers, some with foreign intelligence experience. How specific were

the directions developed by the Communist Party/KGB in establishing VEKSA's pursuits?

KGB officer Paul (Pavel) Toom, head of the 1st chief diretorate of the Estonian KGB (foreign intelligence) compiled a top secret analysis of needs and operational priorities, which were widely distributed among other KGB branches in the USSR. This document was drawn up after the famous 27th party congress in 1986 had been held, where Mihkail Gorbachev had made radical proposals with regards to liberalization, perestroika and glasnost. (Amongst other proposals, Toom suggested that ESTO 1996 should be held in Tallinn, under the strict control of the party and KGB. Ironically the 1996 Stockholm-Tallinn ESTO was successfully organized, but within a democratic, independent Estonia.)

The following is a summary (by LL) of Toom's analysis and proposals in the ‘top secret, eyes only' report, “Working with Estonian 'emigrants' through perestroika”:

Interdependence internationally means we no longer pursue confrontation with other countries, but rather dialogue and mutual understanding. This includes activities with Estonian emigrants. The anti-Soviet efforts of 'emigrant' organizations has been conducted in co-operation with western clandestine services. For this reason we have directed our operations toward gaining information about this partnership and applying counter-measures.

Specifically this meant: placing agents within 'emigrant' centres to learn their operational methods; exposing their ties with western clandestine services; controlling communications channels; compromising their leadership and using other covert tactics. The KGB itself has targeted the anti-Soviet organizations and their personnel, which number a few hundred. VEKSA has been able to form relationships with the more progressive 'emigrants', who are about one hundred, not organized and have not had any impact on the rest of the 'emigrant' community. Tens of thousands of others have been totally ignored by us.

During the last decade the ‘Baltic question' has been on the agenda of many western countries and plays a role in forming their foreign policy. Our attempts to neutralize this have not been successful. It seems we need a new approach both for the 'emigrants' and our tactics. ‘Emigrants' have scored successes at international forums, ‘tribunals', ‘freedom cruises', in lobbying their politicians, etc. Because the 'emigrants' firmly support the justification for the ‘non recognition' policy, the USA gains benefits from the recognition of the pre-war republics as legitimate entities de jure.

To counter this we must use the same methods, to fight for the consciousness, for the hearts and minds of the public. Currently we are infiltrating specific organizations, while the opposition is winning the war of opinions and attitudes. Individual ‘professionals' such as Ants Kippar, Ülo Ignats, Andres Küng, Aleks Miilits (all in Sweden and now deceased) and others have taken the anti-Soviet fight over from the traditional organizations –Estonian Central Council in Canada, Estonian World Council, Estonian National Fund, Estonian Representation in Sweden, etc. (This is Toom's perspective – LL.) ESTO-s, Estivals, Tribunals and other events are the main thrust of their fight. The people involved are more driven by personal ambition or individual agreements with western clandestine services, than they are by belonging to an organization. Perestroika has had a profound effect on their perception of their homeland and the existing Soviet system.

With regards to ESTO-s: Let's grab the initiative and declare that we want to participate, especially with music by Estonian National Men's Choir, Tõnu Kaljuste's chamber choir, Ellerhein's children's choir, two-three rock groups. Music isn't considered to be anti-Soviet and it'll help neutralize the ‘freedom-fighting' political importance of ESTO-s. We won't be able to mobilize for the 1988 ESTO, but for 1992, 1996 and 2000 ESTO – they could all be organized in Tallinn. (It should be noted that for the first time prominent Estonian cultural figures, V. Rumessen, M.Laar, L.Meri, P.-E.Rummo, A. Valton and others were allowed by Soviet Estonian authorities to participate in the 1988 ESTO at Melbourne. Most of them were widely recognized as Estonian nationalists and known not to be party favourites. The KGB/VEKSA combination no longer controlled this participation -LL.)

We should nurture the ties that pre-war 'emigrant' graduates of various schools and educational institutions already have and facilitate their reunions and gatherings. We can boost relationships between county organizations in the emigrant community and their local counties in Soviet Estonia to get a lively reciprocity in activities.

We should facilitate contacts and relationships between unions of writers, composers, artists, theatre professionals etc. We should help in organizing exhibits, concerts, plays of emigrant artists, the publishing of their books, the promotion of their works in general. These ideas have even been discussed within the leadership of the Central Committee of the party. These types of co-operative efforts should also be implemented between groups of engineers, physicians, teachers etc. While practical benefits accrue from western experience and knowledge, it also gives good cover for intelligence operations.

Toom named other sectors, including fund-raising and the disbursements of wills and testaments, where co-operation rather than confrontation should dominate. He stressed that the ‘professional' cold war types can currently speak on behalf of tens of thousands of 'emigrant' Estonians because no concerted efforts had been made to win over the loyalty of ‘neutral' Estonians. By winning over the cultural elite, one can discredit the reactionary anti-Soviet leaders who have, without any rivals, been representing the total community of 'emigrants'. These were Toom's analyses and proposals.

Laas Leivat – Estonian Life No. 42 2012

Well, who outwitted the other? Were they Estonians in exile who deliberately used VEKSA as a necessary door-opener for contacts with prominent cultural figures in Estonia? Or, VEKSA whose one prime goal, amongst others, was to weaken the anti-Soviet stance and activities of the ‘reactionary' leadership of the refugee community abroad and to help promote a more “progressive” relationship with the power ruling Estonia.

The story of Priit Vesilind and his article, “Return to Estonia”, on Soviet occupied Estonia in an April 1980 issue of National Geographic (NG) became an appropriate backdrop to the dramatic stand-off of the two opposing sides of the above argument.

Spanning over 30 years on the staff of NG, Priit Juho Vesilind (b. 1943) rose to the position of the magazine's Expedition's Editor and Senior Writer. With a print run of 12 million, an enormous pass-along readership reputed to be around 40 million readers, NG also enjoyed an unrivaled world-wide reputation for painstaking objectivity, uninhibited by ideology and academic credibility. When the famous 1980 issue was published the Estonian Central Council in Canada ordered several hundred extra re-prints for special distribution to politicians, schools or anyone interested in the subject of Estonia. The NG material was above reproach. This was just one example of the value of the April 1980 issue of NG.

According to Vesilind, the idea for an article about Estonia in the NG originated with Lennart Meri. “One day in 1978 the receptionist at NG's Washington's headquarters called upstairs to tell me that there was a man waiting in the lobby. Dressed in a trench-coat and pork-pie hat, his glasses held together with tape, it was Lennart Meri, then an Estonian writer and film-maker. Meri had noticed my name in the magazine's masthead and decided to check me out. He was then one of a core of intellectuals that was nursing hope for independence. Meri // was determined to get the story into the one magazine whose international authority and credibility were beyond doubt,” said Vesilind.

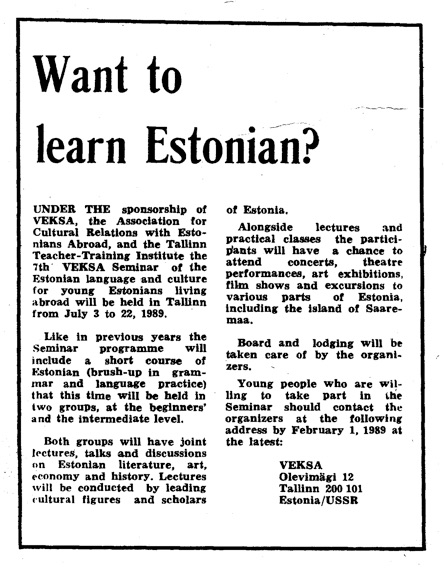

Vesilind indicated that Meri was very pessimistic about any western journalist getting a Soviet visa for that purpose. But since VEKSA organized a summer seminar annually, a participating western journalist could still gather information in that setting without arousing the attention of KGB officialdom. The seminar, to which invitations are extended to youth in the west, was known to be a KGB staged operation. VEKSA's president Ülo Koit sent Vesilind an invitation in 1979 which was kindly accepted.

Vesilind continues: “It was often a cat-and-mouse adventure.. We were escorted by the KGB and Intourist, the arm that dealt with western visitors, but Meri and others managed to provide us with extra trips and interviews, by bald-facedly falsifying our intentions. Toward the end of our assignment, Cotton [Vesilind's colleague] got a telegram from Moscow. It was from Joe Judge, our boss at NG. “Suggest you return home immediately,” he wrote. Judge, in a visit to Moscow's Intourist office, had blown an elaborate cover set up by Meri and other Estonian dissidents [sic.]. Moscow had not known where we were. We were on the next ferry to Helsinki.”

But the story had been written and following its own sense of journalistic ethics, NG sent all who were on pictures or mentioned in the article a copy of the draft to verify facts. Vesilind remembers Gustav Ernesaks cautioning him not to use any names in the atrticle. As a result NG received dozens of letters of denunciation according to Vesilind. The KGB had contacted all involved, interrogated them and ordered them to send letters repudiating everything they had said. Ülo Koit, VEKSA's president and their official host, wrote: “I do not know how you got such an incorrect impression of our homeland. I fear you are giving encouragement to those who are trying to disrupt our country.” (Estonian archivists have claimed not to have found copies of the “dozens” of protest letters from prominent Estonian cultural figures to the media.) The few privileged individuals who had legitimate and KGB sanctioned subscriptions of the magazine did not receive their expected April 1980 copy. The KGB had duly confiscated them at the post office.

But the few that were smuggled into the country were translated and became prized underground samizdat. Translated also was the Voice of America broadcast of the article into Estonia. The ‘Estonian story' had never had such a wide reach, audience penetration and influential platform before. Cultural personalities on trips abroad through VEKSA's programs were eager to obtain copies and take them back as contraband.

Vesilind remembered a rather poignant twist to the story: “The NG article had begun with the words, “Freedom. Only the seagulls have it.” A few months later [after publication] I got a postcard from our Estonian KGB host [sic.], Ülo Koit. “I am standing at the harbor in Helsinki,” he wrote, “watching the seagulls.”

There is no doubt that the 1980 article “Return to Estonia” became an icon, one of the most effective aids in the hands of pro-freedom lobbyists and activists looking for increased support of self-determination for Estonia and its people. VEKSA was convinced that they would benefit by inviting Vesilind to participate in a program totally under their control. Skeptics insist that it was impossible to sidetrack the KGB. Who then outwitted whom?

(Correction: In this column of last week “Veksa: Were exile Estonians its skillful users or being used? (III)”, October 12, paragraph seven contains a typographically mangled and undetected spelling –Koorits – which should be Loorits, the late and famed Estonian folklorist.)

Laas Leivat – Estonian Life No. 43 2012

The ‘positive, pro-Soviet Estonia' support that VEKSA's leadership expected to get from inviting National Geographic's Priit Vesilind to one of their summer camps simply didn't materialize. The April 1980 article by Vesilind turned out to be one of the most useful ‘information packages' that anti-Soviet lobbyists and activists in the West were to use.

One could assume that it was partly Vesilind's personal integrity, the National Geographic's solid reputation of journalistic independence and VEKSA's wild miscalculation of the malleability of individuals democratically oriented. VEKSA knew that dealing with Vesilind and the National Geographic was risky. The summer camps program, presented as sessions of lectures, seminars etc. by well known cultural figures, academics and others, for Western participants therefore could not leave any aspect up to chance.

Archival material as to the clandestine, intelligence gathering, aspect of VEKSA's summer camps is scarce. However, LL in his meeting with Imants Lešinskis was assured by the latter that personnel and operational methods were very similar between that Latvian ‘VEKSA' and its sister organization in occupied Estonia. (Lešinskis was the former chief of Latvia's ‘VEKSA' who defected to the West.)

Lešinskis described the summer camp's preparations as extremely thorough with the expectation of recruiting at least some Western ‘talent' for KGB use. Every single participant from the West was individually targeted. In other words one KGB-connected ‘recruiter' was assigned to one guest. This assured that the profile of the target was accurately compiled – the participants' social/ political irritations, religious leanings, financial solvency, their personal weaknesses (alcohol, gambling, sexual orientation etc.), their strengths (upward mobility in career, reputable alma mater etc.).

The Latvian guests were housed in a large summer villa in the seaside resort region of Jurmala. The building was infested with listening devices. The outside of the building and its grounds were also electronically monitored. With this level of electronic surveillance, the daily reports that the KGB host were expected to submit, the concerts, beer drinking sessions, dances, sing-a-longs and other activities organized for the evening, also helped to gain a good assessment of the targeted subject.

LL asked Lešinskis if such investment in manpower and resources was cost effective. He said they must have seemed that way to the KGB, because the Latvian summer camps lasted for years. He stressed that to recruit a single foreign asset, one had to study and assess a large number of possible candidates, sift through a lot of rejects.

Do the KGB's own files indicate how successful the summer camps proved to be. It is well known that KGB officials, when writing reports of operational activities often tended to exaggerate. Rein Sillar, the Estonian KGB's last chief before the Estonian branch's demise and other high-ranking KGB officers have been asked about the results of their of their recruitment campaigns domestically and abroad. In answering they have always donned a superior demeanour, puffed up their chests in false pride and reminded us of the oath of allegiance given to the KGB, their loyalty to former comrades and an enduring professionalism that forbids them to discuss their previous ‘active measures'. Historians familiar with VEKSA's programs are skeptical that the effort expended resulted in any significant recruitment. In fact many insist that this aspect of VEKSA's goals was an abject failure.

Perhaps more appropriate would be to ask how successful was VEKSA in neutralizing the ‘freedom fighter' potential of exile Estonians who accepted VEKSA's assistance in contacting cultural figures in Estonia. In more specific terms, did people who used VEKSA's auspices in visiting Estonia, avoid anti-Soviet public demonstrations in th West, refuse to sign petitions on behalf of imprisoned dissidents in the USSR or in general distance themselves from any public display that would displease Soviet visa-issuing authorities? Answer: possibly an isolated few.

In fact, in some cases, dealing with VEKSA increased one's latent sense of ‘contributing to the cause'. During the 70's and 80's the Estonian Central Council in Canada was able to send financial support to families of imprisoned dissidents by asking a few of the ‘regular visitors' to act as couriers into the homeland. The task was fraught with danger in that taking unreported cash into the Soviet Union was a criminal offence for which the sentence was severe. This was an example in which the VEKSA connection actually strengthened an anti-Soviet orientation. In another instance an individual who had developed a close relationship with a VEKSA official was able to obtain strictly secret Soviet military documents, which western military intelligence experts valued highly.

Was VEKSA successful in countering and weakening the free-Estonia stance of the ‘reactionary' leadership of the exile community. Answer: not in the least. Did it gain general support in recognizing the legitimacy of the puppet government and its pro-Moscow collaborators. Answer: no. Did VEKSA through its ‘friends' in the West (LL, in studying VEKSA archives in 1993 saw the extent to which KGB operatives falsely claimed the numerous new ‘friends' they had won for VEKSA) make any in-roads in weakening the West's non-recognition de jure of the annexation of the Baltic states. Answer: not at all. Did the very fact of VEKSA's existence manage to disrupt the exile community. Answer: Yes, but only a very limited part of it and only amongst those for whom the issue of visiting or not visiting a captive homeland was ideologically crucial. In any case the last question deserves a series of articles dedicated to that issue.

Laas Leivat – Estonian Life No. 44 2012

Addendum to VEKSA: Unavailable and undisclosed lists of KGB operatives still a vexing problem

Nov 16, 2012 Estonian Life No. 46 2012

The previous five part series on VEKSA concluded that the enormous effort expended in recruiting trustworthy 'co-workers' abroad in the role of sleepers or moles/active agents didn't justify the results achieved. This is not to say that VEKSA was unsuccessful in compiling a comprehensive data bank of individuals to be targeted in the west. In short they were busy as potential 'talent spotters'.

The previous five part series on VEKSA concluded that the enormous effort expended in recruiting trustworthy ‘co-workers' abroad in the role of sleepers or moles/active agents didn't justify the results achieved. This is not to say that VEKSA was unsuccessful in compiling a comprehensive data bank of individuals to be targeted in the west. In short they were busy as potential ‘talent spotters'.

The ‘talent spotters' were forced to be the Estonian writers, artists, musicians, etc. who were invited by VEKSA to be part of a ‘cultural exchange program' with exiles in Canada, USA, Sweden and elsewhere. They had to submit background descriptions of Estonians they would meet on these visits. This was mandatory, otherwise visits to the west would be cut off for them.

Supplementing the amateur ‘talent spotters' were the professionals, who practically always accompanied the groups of artistes. Ironically they were easy to ‘spot' by western counter-intelligence. They were career KGB officers, whose bona fides on their Canadian (or other) visa applications simply did not add up and their cover was easily spotted. Embedded in the cultural groups, they were often listed as ‘attaches' with the ministry of culture or carried some other innocuous title. They actually performed multiple duty on the trips, by keeping a watchful eye on the artistes themselves and by detecting any attempt at recruitment by western services. In addition to the KGB officials, each group usually had one or more KGB informants as fellow travelers, snitches, artistes like the others, who reported the transgressions of their colleagues. (In 1989, when the world-famous Estonian National Men's Choir visited Toronto, when Soviet repressions had eased significantly, when the aggressive stance against the exile community had practically disappeared, when VEKSA's demise was inevitable, travelling with the choir were two professionals KGBers and a few of their own co-opted singers – men who everyone knew as the snitches.)

A definitive answer as to who and in what numbers VEKSA managed to help co-opt ‘co-workers' abroad may never be given. Lists that would aid in this have been either destroyed, relocated or are never to be released. In February 1995 the Estonian parliament passed legislation, whereby individuals who do not voluntarily inform Estonian authorities of their employment or co-operation with the security, intelligence or counterintelligence services or military of the occupying foreign powers between 1940-1991 will have their identities revealed in the government publication ‘Riigiteataja' (equivalent to Canada's Parliamentary Hansard and the USA's Congressional Record). According to different sources some estimate that the government, specifically the Security Police (Kapo) has to date published some 650 names, others insist that the number is in the thousands. In any case the vast majority of individuals revealed were of Russian heritage, working for the KGB in a full time capacity. No agents, no exile Estonian co-workers. The latter were not included in the legislation, unless they had moved to Estonia. It is not part of the public record as to how many actually did inform the Security Police of their KGB background.

Both Latvia and Lithuanian have similar legislation and known former KGB officials who have not had a voluntary ‘chat' with the respective police authorities have been ‘outed'. This fall The Lithuanian Research Centre of Resistance and Genocide published the names and work related details of hundreds of former KGB operatives. These also included names of Lithuanian KGB reserve members. In some instances the term ‘reserve' in this context is the same as it is known in the west – an organized group who have had training and/or actual work experience and have joined a reserve unit (usually on a mandatory basis), ready to be called for duty when required – like in the military. But often the “KGB reserve' may also refer to agents, who have not been career KGB operatives. The Centre is also working on compiling a list of Lithuanian secret co-workers of the KGB for publication. The KGB in Lithuania were not able to destroy or relocate as much of the archival material as in Estonia and Latvia.

The Centre this fall also stated that the head of Lithuania's criminal police service, Algirdas Matonis, has not revealed his KGB past. According to documents uncovered by the Centre, Matonis' relationship with the KGB started in the perestroika years, during a time when subjects were no longer coerced into co-operation. Matonis, who has headed the criminal section since 2005, entered into a KGB relationship of his own free will, the Centre emphasized.

Birute Buraskaite, the director general of the Centre stated that KGB agents had a negative influence on society which may still be situation today. (Here one is reminded that in the Baltic states, the KGB was also universally known as the ‘forces of repression' – repressiiv organid.) Agents/informants could not perform the duties then without KGB interference because they were connected, and still might be today. In their recruitment it was blackmail, use of compromising information against them, help in climbing the promotion ladder in their non-KGB careers that typically assured agreement from the approached potential agent. But, Buraskaite said, they all still had the choice of choosing personal integrity and a clear conscious. It was generally known that KGB threats during recruitment were often hollow.

Laas Leivat – Estonian Life No. 45 2012

In previous articles it has been stated that all who traveled to the West under the auspices of VEKSA were obliged to submit reports of everyone with whom they were in contact. Ostensibly this would fulfill one requirement to be approved the next time they applied for another trip to the west. It was obvious that these reports would help the KGB in the future in their possible efforts at recruiting.

(LL has read many of these ‘talent spotting' reports and their overall effectiveness in assisting KGB recruiters is questionable. Some reports consist of a small list of exile Estonians in the West, some with very little additional information. A few are more thorough, describing personal weaknesses and vulnerabilities such as alcohol use, marital or financial problems that could be exploited. LL in talking to some who did submit the reports, were led to believe the reports were used by the KGB to determine who amongst those exiles visited may have been working for Western intelligence services.)

It has also been stated previously that it is practically impossible to assess the value that can be placed on the reports submitted. Files containing information about the first chief directorate in Estonia (foreign intelligence) started to be relocated to Uljanovsk in 1989, shortly after the mass demonstrations in Georgia. These files presumably would give some indication as to who was recruited. Even though the3 files refer to the recruited agents by cover names only, a description of activities would pinpoint the actual individual in the West. Some 60 files remained in Estonia upon the re-establishment of Estonia's independence in 1991. However the foreign intelligence section of the KGB archives in Lithuania was not depleted to the same extent as in Estonia and 860 files, mostly from the 1960s to the 1980s, were left behind, later to be studied bv Lithuanian historians and the late Indrek Jürjo.

Read the paper sheet No. 46 2012

Sidor på Leht.se

Den stora flykten 1944 8 - 20 nov 2024

80 år sedan flykten 1944

Estnisk Exilkonst 2014

Exilkonst 2016 Ebelingmuseet, Torshälla

Organisationer

Hapsal Vänortsförening

Berättelser

Furusund mottagande

När sovjet upplöste kunde det beskrivas som hänt under ockupationerna som föjlde av andra världskriget.